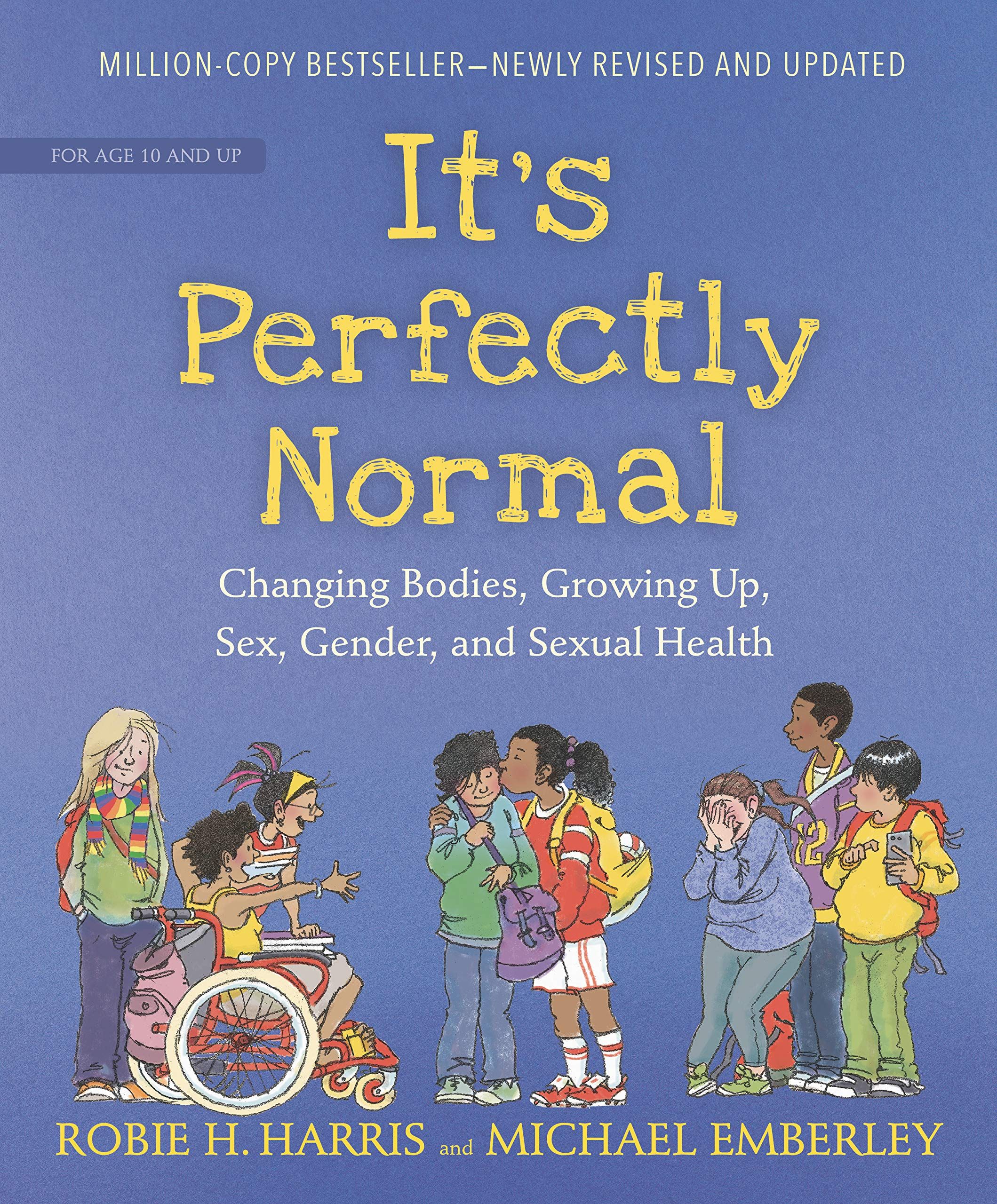

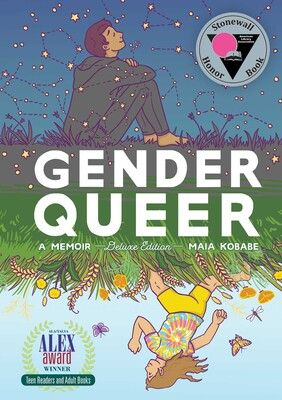

Within an hour of returning home, I saw a post on this very site about how Virginia politicians were suing Oni Press and Kobabe because the book allegedly flouted the state’s obscenity laws. I already knew Gender Queer was fast becoming one of the most widely banned titles in the country, but seeing that post as I cradled my brand new copy in my arms, I felt especially outraged, like an overprotective mama bear. We already know that book bannings have been a lot this year, so much so that Book Riot has been releasing weekly roundups of censorship-related news, in addition to other standalone posts on the topic. As someone who does work in the area of sex ed advocacy, I’m especially agitated. What the majority of these book bans have in common is their focus on diversity, inclusion, and sexuality… lessons our kids really need more of in their lives. There have also been a slew of picture books that, while not explicitly marketed as sex ed titles, have imparted some great lessons on gender and sexuality. And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell, based on a true story, depicts a same-sex relationship between two male penguins and, for this, the book has been frequently challenged as inappropriate for kids. Red: A Crayon’s Story by Michael Hall follows the journey of a crayon who feels they don’t quite fit the label that appears on their crayon wrapper. Hints of gender dysphoria, anyone? Obviously too controversial for kids. When Aidan Became a Brother by Kyle Lukoff and Kaylani Juanita is a cute story about an AFAB child’s journey toward being recognized by his parents as a boy… and about his concerns for the sibling who’s on the way. Obviously unacceptable. From the very beginning, for example, Robie Harris’s books have been a staple of our reading routine. Em has learned about body parts and reproduction from them. She’s learned about families and friends and boundary-setting. Recently, Harris and Michael Emberley released an updated edition of It’s Perfectly Normal. It contains information on conception and puberty, birth control and STIs, and I look forward to reading it with Em in another couple of years. Unsurprisingly, it’s been facing a lot of outrage in the world of those who looove to ban books. Yet my child has enjoyed and understood all of them. Em also loves graphic novels as much as I do, and we always read titles that show a diversity of voices and experiences. One of her favorites is Kat Leyh’s Snapdragon, which stealth-teaches empathy for multiple identities. There’s the single mom who’s worried about placing too much pressure on her young daughter. There’s the best friend who’s exploring their gender identity. There’s the androgynous older lesbian who gave up on love long ago. Snapdragon has shown up on the radars of book banners for all of these reasons. In our house, it’s just a fantastic read featuring folks of varying identities. Then there are the books I plan to pass on to Em later on. Because of recent events, I was thrilled to learn about the existence of What’s an Abortion, Anyway? by Carly Manes and Mar, which was destined to get caught up in the outrage machine. Because someday, Em will prefer to read about sexuality without me hanging over her shoulder, there is Heather Corinna’s S.E.X. (and pretty much everything else they’ve written, all of which has been targeted for possible banning). Because I can’t imagine her ever falling out of love with graphic novels, there is Check Please by Ngozi Ukazu, which is the most charming and delightful story of queer love ever, surpassed only by its sequel, Sticks & Scones. And because I want Em to be aware of the ways in which girls are so casually sexualized, I hope to someday introduce her to Elizabeth Acevedo’s ouevre, starting with The Poet X. I could go on. To read more about why sex ed books are so damn lifesaving, check out Danika Ellis’s post on how these titles don’t “groom” kids; they protect them. Stevenson says it best in his intro to Gender Queer: “Seeing yourself in the world, knowing that you’re not alone, that you could actually have a future as yourself — it’s lifesaving,” he writes. “My parents worked hard to make sure I couldn’t find those positive portrayals. But that censorship didn’t make me not queer. What it did do was make me afraid, lonely, and filled with self-loathing. “I shoved pieces of myself into locked boxes and buried them in the darkest corners of my mind, never to be opened by the light of day … but those boxes don’t just go away. They stay there, radiating pain until it becomes the background noise of your life.”