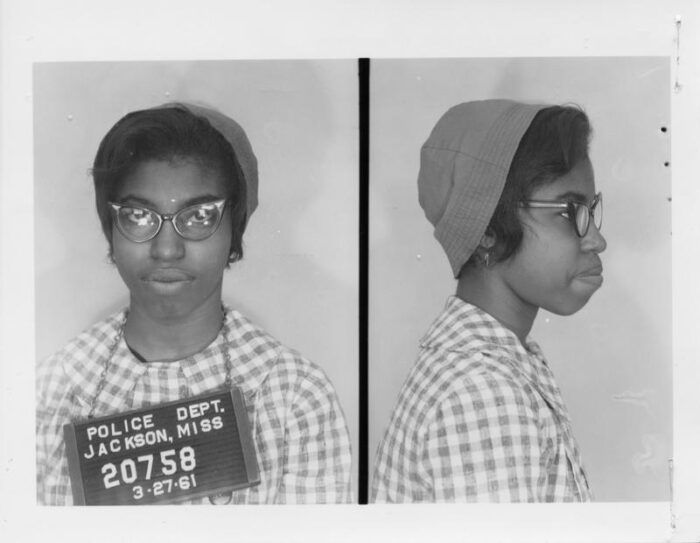

The students then went to the main Jackson Public Library, which was whites-only, found the books they had requested, sat down, and started to read. I had the honor of sitting down with one of the Tougaloo Nine, the group of students who participated in the “read-in” that is intensely under-recognized as a pivotal point in civil rights history. Geraldine Edwards Hollis shared her stories with me, discussing the read-in, its legacy, and her own determination. She first ended up at the Wednesday night meetings, lectures, and discussions with her fellow students because they were held in the building beside her dorm, and the meetings always had coffee and donuts. But she was soon drawn in by her love of learning, as a diverse group of speakers, including civil rights leaders, visited to talk about culture, race, and politics. “I enjoyed reading, I enjoyed learning, and I wanted to find out as much as I could, because in order to do the things that I had as my dream, I knew that I had to do something a little bit different,” says Hollis. “I got started with thinking about the things that I could do to make a difference,” Hollis says. “There were people who were coming to speak at Tougaloo because they could not go to any other area and speak the things that they were speaking.” In the early 1960s, Mississippi was a particularly violent, segregated mire. Local Jackson newspapers worked closely with groups like the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (MSSC) and private arm the White Citizens’ Council, groups that specifically formed to fight civil rights activists and resist school integration. The MSSC had a lot of power in strengthening white supremacy in the state. In this hostile environment, NAACP field secretary and civil rights activist Medgar Wiley Evers and other organizers had to think carefully about how to try and puncture the oppressive weight of white supremacy in the state. Lunch counter sit-ins were a common way to jumpstart movement at the time in other states, but the level of vitriol in Mississippi made NAACP cautious about launching their first action in that format. Instead, they decided to have NAACP Youth Council members sit in at a public library. Libraries were supported by both Black and white taxpayer dollars. They thought that to some of their potential allies, access to public space and knowledge might seem like a more reasonable demand than access to privately owned restaurants or businesses. So it was decided: the public library would be the battlefield of choice. And the nine students at Tougaloo College — including Geraldine Edwards Hollis — were ready for the task. But she knew she had to do this. Her resolve was there — just it had been all of those years as a child, when she’d sneak a flashlight into bed to read late into the night. “When you have a passion to do something, you find a way to do it,” Hollis says. Hollis herself was apprehensive. “I knew the results of what had happened to many people in that particular state, in the town that I lived in,” she says. “I knew the governor at that time. I knew of him and his desire for a white-only state or a segregated state.” On March 27, the nine students first went to the “colored” library and asked for books that they knew weren’t there. Once they had confirmation, the nine went to the other library, the whites-only public library. They entered the library, got the books they needed, and sat down to read. The library staff called the police. All nine students knew that they could be arrested and beaten, and that their actions could put their education and families on the line. All nine had been trained in nonviolence. Hollis knew that she “would listen, and that I would follow orders only after I had done the things that I came to do, which was to sit in the white only library in the city of Jackson and secure a book that I knew that the other library did not have, to be on target with the fact that I had a reason being there and a reason to want to read that book in the library.” She had dressed carefully, in layers for the variable, early spring weather and in low-heeled shoes she knew she could run in. “In my spirit and my body and my effort, I was ready for the occasion,” says Hollis. “We had an idea that we were going to be arrested, but we didn’t think that we would be jailed, and that we would be jailed for that amount of time,” Hollis says. They were held for the full days up to their trial, and interrogated extensively. “They wanted to know who made us do it,” Hollis says. “Each one of us was interviewed by a policeman or several to try to get in our minds and make us say something we were in denial of.” They wanted to hear that the nine had been put up to the whole thing, and they wanted an outside agitator to blame. But all nine denied having a leader or instigator. On March 28, the nine Tougaloo students met with their college president, Daniel Beittel, who was supportive (the MSSC would later help pressure him into a forced resignation). None of the nine students were allowed to speak to their lawyers, Jack Young and R. Jess Brown, before their trial. This demonstration only lasted 40 minutes. College president Jacob Reddix appeared, threatening to expel student protestors and allegedly assaulting two of the students. The crowd was dispelled with police violence — clubs and dogs. “They were very, very upset,” says Hollis. “They came out to protest because you would think that reading would be something they would allow you to do.” The next day, 50 Jackson State students set out to march peacefully to the jail in support of the Nine. “Many of them wanted to let it be known that they were supportive of the fact that we chose to put our schooling and our lives and our families in jeopardy to make things open up for the general public — not just for Tougaloo, not a handful of students, but for the whole of that area,” says Hollis. They never got to their destination. Police converged on them with tear gas, clubs, and dogs. The police would tell the press that the backlash was because no parades were allowed without a permit. (At that same moment across town, thousands of white Mississippians, including the governor, were holding a parade celebrating the state’s secession from the Union, many of them decked out in Confederacy symbolism and regalia.) When the Nine arrived from jail for their trial, the crowd burst into applause, at which point the police pounced. Evers and several women and children were beaten, two men were seriously bitten by dogs, and an 81-year-old man had his arm broken by a police club. “There was violence,” says Hollis. “Some of the people got hit with billy clubs and injured — which we thought going into this might have happened to us.” Inside the courthouse, all nine students were convicted of breaching the peace. They were fined $100 and given a suspended sentence of 30 days and a year’s probation — which was contingent on them not participating in any demonstration or protest for 12 months. But despite the continued violence, threat, and intimidation, Hollis remained in Jackson to complete her education. “I was determined to have all of my education done,” says Hollis. She had worked hard to get her degree on a fast-track program, and was determined to complete it. She graduated in three years, with degrees in physical education, biological science, and mathematics. It was a lonely road. “I persevered, although there were some lonely times, some difficult times,” she says. “I worked in the buildings to help with my tuition. I didn’t have the luxury of not finishing my education. So I was determined to weather it out, and that meant I went to school during that time and three summer sessions in the heat.” Tougaloo would continue to play a pivotal part in civil rights movements in Jackson, Mississippi for a long time — from a sit-in at Woolworth’s, a series of boycotts of discriminatory white businesses, pray-ins at white churches, support for the Freedom Riders, and more. President Beittel, who had supported the Nine, was later forced out by racist pressure. Nevertheless, Tougaloo College would survive — whereas the MSSC closed in 1973 — and it continues to be a force for civil rights and historical awareness. Medger Evers would go on to fight for education access, lead boycotts and voter registrations, work for economic access, and more in the battle for civil rights before being assassinated in 1963 by a member of the White Citizens’ Council. “There was so much negativity and disdain in Mississippi at the time,” Hollis says, “until it was something you just didn’t even want to talk about, let alone try to do anything else. But Medgar Evers continued to do these things anyway.” Hollis remained connected with him for years, because she wanted to see a change in Mississippi. Medgar Evers was the Nine’s mentor, and crucial to civil rights change and progress in Mississippi and the U.S. at large. The Tougaloo Nine had a significant and fairly rapid impact on public access in the United States. In 1962, the American Library Association adopted the “Statement on Individual Membership, Chapter Status and Institutional Membership.” It said that membership in the ALA was contingent on their chapters being open to everyone regardless of race, religion, or personal belief. Four state chapters withdrew from ALA as a result — Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Although retirement might be a strong word. Hollis has toured the U.S. as an author, recounting her life and its lessons in Back to Mississippi and March Memories, as well as a lecturing and speaking. “The change of tide in Mississippi began with the Tougaloo Nine,” said Myrlie Evers-Williams, activist and widow of Medgar Evers — yet there was little acknowledgment of their impact for decades. Even as Mississippi started acknowledging its civil rights heroes, it took Hollis speaking up — loudly — to get the Tougaloo Nine included in their lists and honors. “I am outspoken because I am the only girl of five brothers, the oldest,” she says. “So you don’t mess with me. If you wanted to outdo me, you had to out-wrestle me — which they couldn’t do. So I went to Mississippi and made sure they knew we were there and were pioneers.” But overall, not enough people know of this important contingent of students who made a massive impact in the fight against white supremacy. — Jackson Advocate (@JacksonAdvocate) July 18, 2022 On the occasion of the read-in’s anniversary, Bradford said: “It seems that everybody is being celebrated and praised for their fine work except the very people who launched the civil rights movement against some of the greatest odds ever faced by man or beast. I’m not saying that the Tougaloo Nine should be rolled out like world-conquering heroes in a ticker-tape parade every year, but they should at least be acknowledged, along with many others, whenever a purported celebration of civil rights activities in Mississippi takes place.” I hope you’ve been enlightened as well. These Nine are particularly relevant in light of modern-day movements against police brutality and against repression and discrimination in public spaces and in knowledge access. “All of my life, I’ve been trying to teach those that I work with how to be the best that they can be under whatever circumstances they are in — that you can overcome if you desire to,” she says. “My goal is to enlighten, and I continue to do that.” Certainly there are a lot of civil rights pioneers within a movement that was driven by grassroots activism and hundreds of people putting their lives on the line. And not all of them will receive coverage. But I was still surprised to find this story resting where I hadn’t been able to see it before. Librarians are a rebellious lot. Librarians are warriors fighting for free and unfettered access to public space and to knowledge. They fight against book bans and work to get books in the hands of our youth. So I know librarians want to know this story. I know they want to feature and honor the Tougaloo Nine who helped make libraries a public space for all, as they should rightfully be. So go, readers, go, librarians, and go, teachers! Spread the word about the Nine that jump-started civil rights in Mississippi and paved the way for the unfettered access to public houses of knowledge in the United States.