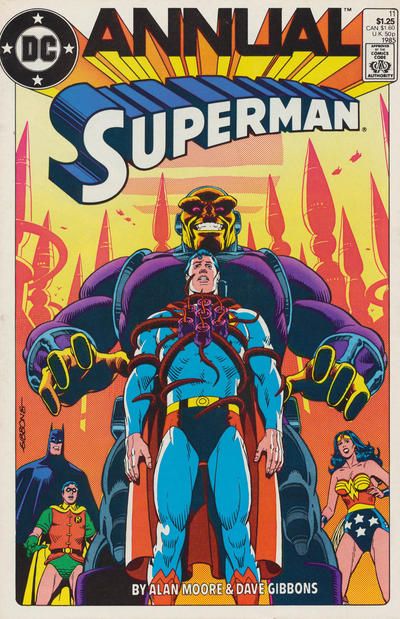

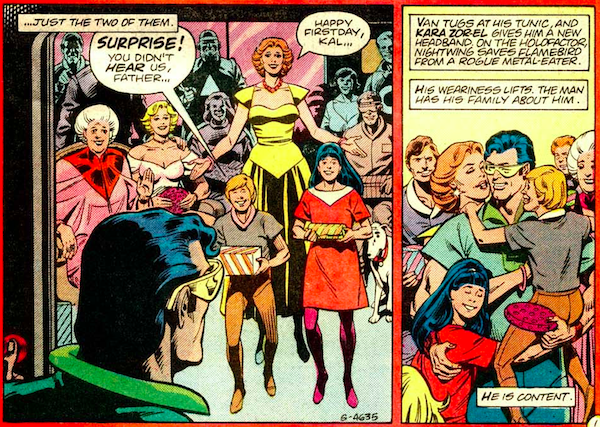

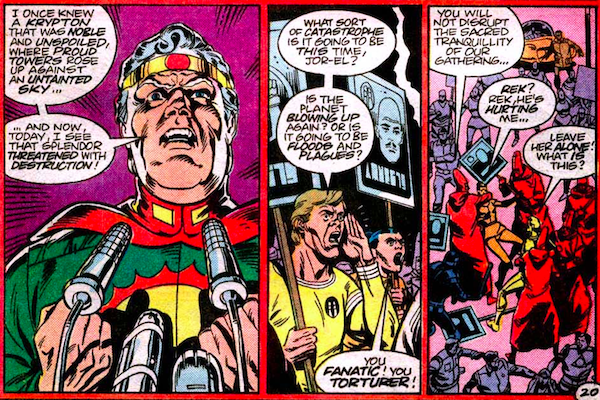

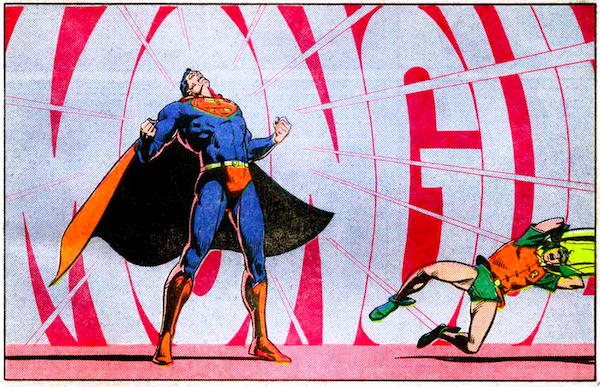

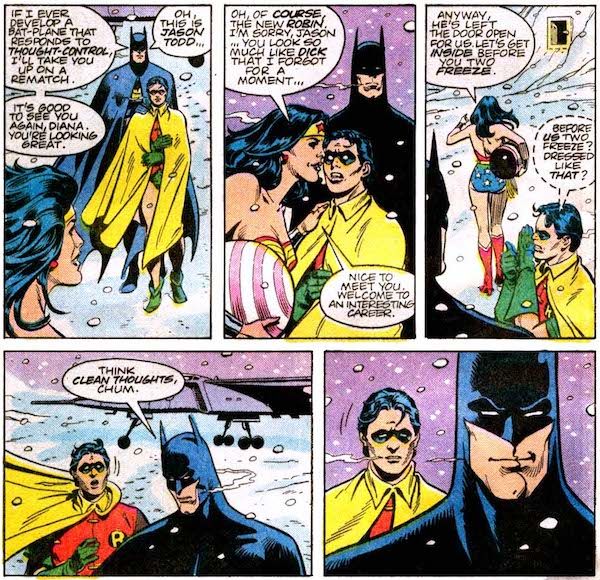

I watched the JLU and Supergirl adaptations of the story when they aired, but despite being a huge Superman fan, I only recently read the original story, and was somewhat surprised by what I found. So how does it hold up? Let’s take a look! The basic plot of “For the Man Who Has Everything” is simple: it’s Superman’s birthday, and Batman, Robin (the Jason Todd version), and Wonder Woman arrive at the Fortress of Solitude to give him his gifts. When they get there, they are horrified to discover Superman standing transfixed in the middle of the Fortress, with a strange alien plant apparently growing through his costume and into his chest. As they try to figure out what it is and how to remove it without hurting Superman, the alien warlord Mongul, an established Superman villain, reveals himself. He sent the plant, which is called a Black Mercy, as a trap disguised as a birthday gift. “It attaches itself to its victims in a form of symbiosis, feeding from their bio-aura,” he explains, and in return, “It gives them their heart’s desire…It reads them like a book, and it feeds them a logical simulation of the happy ending they desire.” So what is Superman’s heart’s desire? The story cuts back and forth between the Fortress and the dream world the Black Mercy has created for Superman. We see Kal-El on a perfectly intact Krypton, happily married to Lyla Lerrol, a Kryptonian actress who was first introduced in a 1960 story where Superman travels back in time to before Krypton’s destruction and falls in love with her. In this dream universe, they have a son named Van and a daughter named Orna. Kal also has an arduous job at the Institute of Geology, which I guess is Superman’s secret dream career? That’s sort of a curveball, but okay. Almost immediately, however, we see the cracks in Kal’s perfect existence, primarily centered around his father. See, Jor-El still predicted that Krypton would explode, but since it obviously didn’t, he was forced to resign from the Science Council in disgrace and has become a bitter, conservative reactionary, railing against drugs and “racial trouble” with immigrants, as well as popular pushback against incarceration in the Phantom Zone — a method of punishment which he invented. Lately, he’s cozied up with the ominous-sounding “Sword of Rao sect” and the “Old Krypton movement.” After speaking with his father, Kal is called to the hospital by his aunt Allura; his cousin Kara (Supergirl, in his waking reality) has been attacked by anti-Phantom Zone protestors and is in critical condition. Since she was targeted for being House of El, Kal decides it’ll be safer for his family to leave the city, but as he and Van head out, they come across an Old Krypton rally, with Jor-El spewing a fascist-tinged speech. Kal then drives to the crater where the city of Kandor used to be, hugs his son, and tearfully tells him that though he loves him, he’s pretty sure Van isn’t real. Meanwhile, back in the Fortress, Wonder Woman is fighting a losing battle against Mongul while Batman attempts to pry the Black Mercy off of Superman’s chest. It finally comes free just as Kal confesses his confusion to Van, and the false Krypton crumbles as the plant lands on Batman’s chest and begins feeding on him instead. Surprising no one, Batman immediately starts dreaming of a world in which his parents weren’t murdered, while Robin fills a furious Superman in on what exactly is going on. Superman flies off to confront Mongul, who gloats over the suffering he just put Superman through: “Escaping [the Black Mercy] must have been like tearing off your own arm.” As they fight, Robin gets the Black Mercy off of Batman’s chest and drops it neatly on Mongul’s chest, taking him out. The story ends with awkward wrapping up: Superman plans to drop Mongul into a black hole; he and Wonder Woman kiss for some reason, after which he says “Mmm” (gross); and he finally gets his real birthday presents: a model of the Bottle City of Kandor from Wonder Woman, and the surprisingly romantic gift of a special breed of rose called “the Krypton” from Batman. The last page shows Mongul, dreaming of bloody conquest, perfectly content. I don’t think I’m suggesting anything shocking when I say that Alan More and Dave Gibbons are, like, pretty good at comics. “For the Man Who Has Everything” is a well-told and beautifully drawn story, with incredibly striking panels and splash pages. It’s interesting and readable. But what struck me, upon finally reading the original telling, was how it completely fails to live up to its central premise. The Black Mercy is supposed to give Superman his heart’s desire. Now, this is a pre-Crisis Superman, one who looked at his Kal-El/Superman persona as his real self and Clark Kent as a disguise, so it makes total sense that his perfect world would be a non-exploded Krypton. What doesn’t make sense is that his life on Krypton is…pretty lousy? Sure, he’s married…to essentially a one-off character he fell in love with 25 years ago who has no actual personality. His job, which his father looks down his nose at, has him working from dawn to dusk, to the point of physical pain. Krypton is plagued by unrest, and his extended family is at the center of it. His father goes from “miserable crank” to “burgeoning space Hitler” in a handful of pages. His cousin gets stabbed and his mother is dead. What kind of utopia is this? The central conceit behind the Black Mercy is that the victim is perfectly capable of breaking its hold, but would never want to. But the world we’re shown isn’t the irresistible fantasy that would make that true. It starts out with drudgery, and descends into violent chaos. The Black Mercy is, it would seem, bad at its job. Except, when the Black Mercy lands on Batman, the fantasy world he’s given is exactly what we would all imagine he would want. And Superman’s rage towards Mongul when he’s freed implies that he’s had something precious dangled in front of him and then taken away. So what is he seeing in his dream world that’s so valuable? What element of it are we supposed to read as his heart’s desire? The answer is in the most powerful and heartbreaking panels of the story: when Kal kneels in front of his son and tells him, “I don’t think you’re real.” Even though I find the story around them hollow, these panels pack one hell of a punch. Superman’s heart’s desire is to have a son. (Don’t worry, bud, you’ll check that box off in exactly 30 years from this story, if you don’t count your semi-neglected clone!) But that being the hook just highlights the essentially patriarchal nature of a story that continually disregards its female characters as collateral damage and sexual props. Let’s pause for a minute here to take a look at the Justice League Unlimited adaptation of this story. The plot is functionally identical, although there’s no Robin, and it’s Wonder Woman who gives Superman the rose for his birthday, while Batman awkwardly offers cash. (I will never be able to decide whether I prefer a sentimental Batman cultivating a unique rose for his bestest buddy, or a horrendously undersocialized Batman handing over cash because he doesn’t know how to people. They’re both so good.) The conceit of the Black Mercy hangs together much more strongly in this version, since Krypton isn’t plagued by unrest, but by seismic activity that only Clark notices, and that is exacerbated by Batman’s attempts to get the plant off of Clark in the real world. Clark is living a genuinely lovely life, not an incredibly stressful one. However, he’s married not to Lyla Lerrol, who doesn’t exist in the animated universe, but to a dream creation named “Loana” who is very visibly a combination of Lois Lane and Lana Lang. That is, to put it bluntly, hella effing creepy. Women aren’t interchangeable collections of pleasing physical traits, and the idea of mixing and matching pieces of two incredible characters (animated Lana is probably the best Lana out there, and Lois is Lois freaking Lane) to create a “perfect woman” is misogynistic and dystopian in the extreme, not to mention beneath Clark. But this is very in keeping with the original comic, which presents Father Knows Best-style suburban wedded bliss as the pinnacle of happiness, regardless of what we know about the characters. Kal is married to a woman he barely knows, who we’re told gave up an acting career to settle down with him. Bruce, in his fantasy, is married to Kathy Kane (Batwoman), who he spent the Silver Age desperately avoiding. The presentation of happiness as suburban domesticity is so unconvincing that it almost feels like Moore is deliberately interrogating it as essentially hollow — but doing so undercuts the very principle of his story. The Black Mercy creates its victims’ perfect world, so this must be perfection. “Lyla, why did you ever give up acting for this?” Clark asks at one point, early in the fantasy. “I don’t know, Kal,” she replies. It’s meant to be playful banter, but when you start prodding at the emptiness of the female characters’ lives in this story, and the lives men imagine for them, it starts to read as chilling. Because even outside of these Stepford marriages, the women in the story also entirely lack interiority. Kara, the most important female character in the Superman franchise after Lois Lane, is unconscious for two of the three panels in which she appears, so she obviously doesn’t have any lines, opinions, or personality. Lara is dead. It’s also extremely telling to me that Diana never has the Black Mercy fasten on to her, because that would require showing us what Diana’s perfect life would be, and that’s not a question Alan Moore seems interested in or even capable of answering. Diana even says at the end of the story: “I’m a little envious. It must be wonderful to find out just what your heart’s desire really is.” In other words, it must be wonderful to be treated like a complete person, and not a prize for Superman to arbitrarily kiss after Robin defeats the villain for him. Mmm, indeed. And then there’s Orna, Kal and Lyla’s daughter. Like Kara, she has no lines. She’s not present for the gut punch moment at the end when Kal tells Van he isn’t real. She’s so unimportant to Kal’s emotional arc that she wasn’t even used for the animated adaptation; Van is an only child in that. And I can’t even blame the show’s writers, because they’ve boiled the story down to the essence Moore gave us: to have a son is all that is required to create a utopia, regardless of what that means for your wife, mother, daughter, female cousin, or planet. The Supergirl adaptation, as you might imagine, handles things significantly differently. The details of the surrounding plot are obviously changed — the Black Mercy is sent not by Mongul but by Non, a Kryptonian villain working for Kara’s aunt; the setting is the DEO and not the Fortress of Solitude; there’s a wacky subplot with Cat Grant, etc. Kara’s allies are even able to send her sister Alex into the dream world to try to pull Kara out of it. Crucially, Kara’s fantasies of Krypton make sense. Unlike Superman, who came to Earth as an infant and has no memories of his home planet or biological parents, Kara lived on Krypton until she was 12 (in the show’s timeline). She remembers her parents. She remembers the culture. Having her home restored is a logical utopia for her in a way that it isn’t for Superman. And it is the depth of the relationships between women that the episode revolves around, as so many episodes of Supergirl do: Kara’s love for her late mother Alura, which tempts her to stay in the fantasy; the strength of her bond with her sister Alex, which pulls her back to reality; and her complicated relationship with her villainous aunt Astra. No one-note Stepford wives here! Supergirl is by no means a perfect show, but I can’t imagine a single female character on it ever musing about how nice it would be to know what their heart’s desire is. The women of Supergirl are allowed to want. On a technical level, the original “For the Man Who Has Everything” is a brilliantly told story. But what could be a great hook falls apart completely with any close reading, because it never delivers on the promise of its premise, and because the utopia we’re presented with is a trite shorthand for happiness instead of anything germane to the Superman we know. The closer you look at how Moore treats women, the more this weakness is exacerbated. The JLU adaptation, by hewing closely to the source material, improves upon but never quite escapes those issues, while the Supergirl adaptation uses the original hook to build something new and character-driven, and is far more successful on an emotional level, even if the execution isn’t quite as polished. Like I said at the start of this, “For the Man Who Has Everything” is a classic. If you’re looking for a list of Superman stories to read, it will inevitably be recommended to you. I’m not saying we shouldn’t keep reading it, but I am saying we need to start taking a closer look at the rote, male-dominated comics canon of the 1980s to see whether or not it holds up, rather than reflexively recommending the same things that are always recommended — and start recommending more inclusive stories that might perhaps start from the same premise, but take the time to bring humanity to everyone in them.