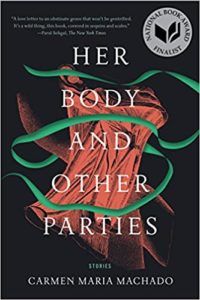

The modern haunted house can be traced all the way back to the gothic novels, with its foggy landscapes and towering dark façades and evils that are intrinsically connected with the nuclear family (e.g. a wife in the attic or an abusive husband). It has been noted, also, that these types of novels tend to have themes at the center that are highly dedicated to ‘women’s issues.’ Horror in general, no matter how alienating towards women, through murder, torture, or gore, has had mainly a fan base of women as women have always, in one way or another, been at the center of these narratives. If you are not convinced, don’t take my word for it, author Sady Doyle’s Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers goes into detail about how women were made to look monstrous or adapt to the monstrosity around them all throughout pop culture. So it’s no surprise that the origins of these dark tales took place in spaces traditionally assign as feminine. However, what I really wanted to talk about today is how the home became such a space in our modern conception. More specifically, how the queen of horror, Shirley Jackson, created the blueprint for the modern haunted house, cementing for future generations of writers and readers the deep anxieties of marriage and family and domestic spaces as environments in which women not only find their deepest fears but also find their greatest strengths. As we are all staying home now with the whole pandemic thing, I have weirdly found myself at times both deeply comforted as an introvert, and terrified as someone who has to deal with chronic anxiety. I have always found horror novels, more specifically Shirley Jackson’s novels, in the Venn diagram of those experiences. Last month, I decided that I wanted to read The Haunting of Hill House, one of Jackson’s few titles that I hadn’t yet read. And let me tell you this was long overdue (also uncalled for when I have to stay inside all the time, but hey I like to set myself up for failure like that) and now I can only think that my entire apartment is slowly tilting to one side, making me see things differently. And that is because there is something particularly horrifying about houses, more specifically about homes. If you grew up with cousins that loved telling ghosts stories and watching horror movies and true crime shows, you most certainly have looked at your siblings, parents, and that chair in your room where you put all your laundry in a terrifying way when the shadows hit it just right in the middle of the night. No? Ok, just me then. But anyway, no matter how horrifying those stories were to a young me, they were also fascinating. Suddenly I saw how intricate relationships could be, how interesting the domestic lives of people, specifically of the women around me, could be. Horror novels taught me about abusive relationships, and gaslighting, and how much power there is in owning one’s space. Shirley Jackson is the master of the genre; in my opinion, her stories have always focused on the topics of family and home. And given Jackson’s actual life, this is not surprising. Besides being a writer, she was a mother who raised her children without any help from her emotionally abusive husband, and she was the only homemaker in her family, which, later, because of her writing, also included being the primary breadwinner. In many parts of Jackson’s life, she was constrained to domestic spaces by no want of her own. Like many other writers before and after her, she was forced to navigate a society that did not value the work she did, both as a writer and as a homemaker. Famously, she said that when she gave birth to her second child and the nurse asked about her profession, she answered writer, to which the nurse promptly replied, “I’ll just put housewife.” Ultimately, in both her memoir and in several interviews, it is clear to me that Jackson was not fulfilled by her position as a mother and wife, and this dilemma is clear in her fiction. To me, right now, one of the most interesting things about Jackson’s work is how much her writing seems to be rooted in the many experiences I have been having in quarantine. The domestic is Jackson’s territory. Her horror does not come from monsters in the underground or aliens in the sky. It comes from inside the house. Family is a complex facet of that; relationships in private spaces take dark turns and display the truly awful ways we can all be scary. To me, a good example of that is the relationship with the physical house that the protagonists in her two most famous novels have. In We Have Always Lived in the Castle, the house’s walls start to deteriorate as the book moves on, and the relationship between Merricat and Constance becomes distant. It is also at once a space of safety for their family from the prying eyes of society but also the place in which horrific acts of violence have been committed. The same goes for Eleanor in The Haunting of Hill House, as the house itself seems to adapt to Eleanor’s desires for companionship and purpose. However, it also manipulates her mind, disorienting her to create a narrative of entrapment. By the end, when she is forced to leave, she does not want to because the house has given her a space in which she is not neglected or undermined. Basically, Eleanor starts to feel that the house wants her, what that might mean in terms of the actual horror (is the house accumulating souls?) is left to interpretation. Nonetheless, it is clear that Eleanor has found a sense of purpose in being haunted. In my experience in quarantine, that sentiment rang very true to me. Domestic spaces in mainstream media have been defined by their coziness and family happiness. However, the reality is that as much as homes can be shelter, they are also where we show both our most damning sides and where too many of the most horrific things happen. In researching Jackson, this seems to have been a clear dichotomy in her life. She was unfulfilled as a homemaker. She did not seem to find purpose in motherhood. Her relationship with her husband was clearly emotionally abusive, given the many affairs he had and his deep-seated arrogance and hurt pride when she became the main provider through her work. It is known that he would humiliate her to his colleagues and diminish her achievements, because of the subject of her writings. I am not the kind of person that tends to overtly analyze an author’s life and go scavenging for clues in their fiction. This is partly because I think it takes away from my enjoyment as a reader, and partly because I don’t have all the information and I don’t like to assume anything that might demerit their work. However, during his time, I began to understand Jackson’s inspiration, or at least I think I have because I have come to see the impact that domestic horror has had in my life. I have had very emotionally abusive relationships in my past. Even now, as I am in a stable and healthy relationship, I find the memory and anxiety caused by those past experiences creeping into my life. I’ve had bad boyfriends, demanding parents, and friends who frankly did not earn the title. Like most people, I am shaped by the traumas that occurred in those relationships. Even as I have overcome most of them, they still linger in the way I understand my creative process and consequently, my self-understanding. Maybe, I then figure it’s because of those things that I am drawn to Jackson’s work. Her horror is not soft, but it is defiantly quiet—relying on her main characters’ inner experiences to shape the world. Be it abusive parents or spouses, the women in her novels are always dealing with some form of familial abuse, which in turn has them seem monstrous. Most importantly for me, though, they are never victims, at least not in the common sense. Yes, they suffer, and yes, sometimes they die, but there is a line between outside and inside horrors. They are always in some way in control. Merricat poisons her family and Eleanor puts others in danger, but both of these acts are so ambiguous in their nature that you, as a reader, never truly see them as villains. They are part of the horror around them, not the cause of it. In this respect, I feel there is a lot of power in these stories because they navigate the subtle relationships we all have with ourselves. I don’t believe anyone should be ostracized for their past or their struggle with mental illness, but these things should also not be used as carte blanche for you to be an asshole to other people, and I had to learn this the hard way I’m ashamed to say. What I’m trying to get at is that like no other writer of her time, Jackson also understood how hard it was to live with and have to deal with these issues daily, be it certain forms of stress disorders or depression. Her characters seek acceptance. They are excluded by the society in which they grew up. They are overlooked and, in some instances, literally murdered by it. They are all women, in domestic situations, who are either put to death by their families, in ritualistic ways, or they are the ones doing the killings. But at all times they are at the center. Going back to Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, Eleanor’s connection with the house is a terrifying and powerful thing that ultimately gets her in trouble. In all of Jackson’s novels, there is an explicit connection between the main characters and their homes. Most importantly, this connection is used as a terrifying external demonstration of the character’s state of mind. Eleanor, for instance, experiences the same phenomena as everyone else in the house. However, because it seems to be directed at her, we are made to think that the house only wants her. Thus when her connection with it eventually comes to a forced end, we are left wondering if the paranormal events actually happened. This questioning of Eleanor’s sanity is not only a facet of the Hill House storyline, it can be found in most of Jackson’s writing. This narrative style, clearly influenced by the many gothic writers of the 19th century, is not new or exclusive to Jackson. However, her contributions to literature and the horror genre is unparalleled to this day. Jackson was a revolutionary of social critique. Although many still believe she is only famous for The Lottery, she is responsible for the modern psychological thriller phenomena and the wave of feminist horror we see today. Jackson has inspired other artists like Carmen Maria Machado and Mike Flanagan. In her wonderful collection of short stories, Her Body and Other Parties, Machado uses the same narrative structures and settings to discuss abusive queer relationships and her experience as a woman of color in the modern world. On the other hand, Flanagan, who used Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House to create the base storyline for the Netflix show of the same name, expands on Jackson’s tropes and worlds by using Hill House to discuss grief, family dynamics, memory, and mental illness explicitly. Although the series is more of a reimagining of the book, it is still one of my favorite examples of Jackson’s work used as inspiration for a series, rather than a proper adaptation. Flanagan explicitly shows his admiration for the original text and adds his own personal interpretations of the same themes addressed in the novel. So, if you are looking for some meditative horror or just comfort in knowing that you are not alone in your experiences with domestic trauma or just relatable discomfort at this time, I recommend you explore some of Shirley Jackson’s catalog. The impact that literature can have on how we understand ourselves still amazes me every day. In this time where everything is so uncertain, I think it’s important to look for books that allow us to feel bad feelings without judgment. Yes, this is an anxiety-filled time. Yes, the world is a scary dumpster fire, and yes, it is frustrating to most of us that we can not take any meaningful action to stop this besides being home. It is okay not to be okay, and if you want some connection or empathy in these feelings or just some relief that at least your house isn’t haunted and no one poisoned the sugar, look to Shirley Jackson.