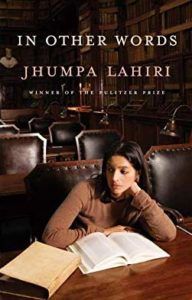

There is one chapter in particular from When Languages Die I found myself thinking about years after I read the book. In it, the author shares what he learned from the last speakers of the Tofa language of Siberia. Confronted with social pressures, young speakers had abandoned their ancestral language. Harrison explains that “Many factors can interrupt successful language transmission, but [it] is rarely the result of free will.” Instead, he suggests, the loss of a non-dominant language is sometimes the result of speakers as young as 7 years olds who, due to social pressure, choose to speak the more dominant tongue and leave behind the language of their parents. When my son turned 6, I began to panic. I figured he would soon stop speaking Spanish to me, and his brain would be filled with the English words he exchanged with friends at school. I doubled my efforts and made sure he and I only spoke Spanish to each other. When he was little, I used to pretend I did not understand when he said something in English. I would ask “¿Qué?” or say “No te entiendo,” and he would translate the idea into Spanish. Eventually, he figured out I was an English professor and that it wasn’t that I did not understand, but that I wanted him to keep practicing. For years, I continued to ask “¿Qué?” and he continued answering in Spanish. In spite of my efforts, by age 12, my son’s strong language had switched from Spanish to English. We spoke Spanish at home, and he read books by Latin American authors. He had a good vocabulary in both languages, but English always came more naturally to him. I realized something had happened at this stage that I had not understood from When Languages Die: It was at this stage, in middle school, when the language of his generation was taking shape. My son and his friends were using and inventing phrases that were not part of my husband’s vernacular, whose first language is English. Their communication was shaped by the TV programs they watched, the video games they played, the books they read, and the music around them. It was only natural he would become protective, even without noticing, of the language that housed the words and jokes so closely connected to his identity and his social life. The other thing that happened around that time was that I was tired. For over 11 years, I had been in constant competition with my son’s environment. I had lost battles every day to shows that didn’t sound good dubbed in Spanish, to jokes that were not funny in Spanish, to songs we sang in English. I had spent a lot of time searching for books not only in Spanish, but Spanish from Mexico. He read them, almost as a favor to me, patiently, with the same patience, in fact, with which he did his homework. The fact that learning and keeping my language was a chore to him hurt me and debilitated my efforts. I realized it was not the children who were killing the languages; it must have been the exhaustion of the parents that caused languages to die. The feeling of defeat after a decade of trying to convince their children that the second language was also cool, that it also had funny jokes, and that it could provide a valuable way of looking at the world was draining. I had done my best to incorporate my culture into our everyday lives, and my son knew the names in Spanish of everything that surrounded him, but there were so many things with cultural value that did not exist here. Words like mercado, quiosco, yunta, petate had no particular reference to his world. I read In Other Words by Jhumpa Lahiri around the time when I recognized there would always be a crevasse between my son’s Spanish and mine. I read and reread passages that resonated loudly with me. Reading Lahiri, I realized part of the problem was a kind of nostalgia I was feeling at that stage of my life for what I had lost. When Languages Die had not prepared me for this stage, because in their studies they had looked at rural towns in the outskirts of big cities that had a different dialect. In their small communities, the adults at least had other adults who spoke their language. Plus, they had not lost a connection to the objects and places from their childhood. As an immigrant, my experience was very different. Not only was I tired of trying to convince my son of the coolness and importance of Spanish, but I was also mourning what I had left behind. Eventually, I understood that my son could not visit the place I grew up, with all its particularities and with all the things I loved, because that place no longer exists. Time has taken over it with new conditions and even with a new way of speaking. But I have also realized that this loss is something all parents may feel; it is not particular of immigrants. The places where we grew up and the words young people use have changed. Once I recognized it is not only because I am far away from my land that my language may sound foreign to my son, I was able to continue my quest to keep Spanish in his life. He may not always use the same words a young person his age in Mexico would, but he is learning my language, and that is still a great gift. Lahiri writes, “When the language one identifies with is far away, one does everything possible to keep it alive. Because words bring back everything: the place, the people, the life, the streets, the sky, the flowers, the sounds.” Every day I pick something different to bring for my son from a faraway city in the north of Mexico. It’s fun to make things and concepts travel. I choose words as if I was selecting gifts I pick from a shelf. For today, I have chosen “cobijar,” which means to protect or provide shelter, but it also means to put a cozy blanket over someone for warmth.