In Catherine Spooner’s Contemporary Gothic, the author describes gothic fiction as a genre especially full of self-reference. In particular she says the literature is “cannibalistically consuming the dead body of its own tradition.” It truly doesn’t get any more gothic than defining gothic literature with such a spectacularly gothic metaphor. Jane Austen may be furthest thing from a forgotten corpse (sorry, Jane, that came out wrong). But she did consume seven of the lesser-known works in the genre, giving them a fascinating legacy.

Austen and Gothic literature

Natalie Neill pointed out in her article about Northanger Abbey and gothic novels from the 1790s that Jane Austen’s entire life’s work offers “slanted readings and pointed revisions of an inherited body of literature which has now fallen largely into obscurity.” It makes complete sense, then, that Austen’s first completed novel, Northanger Abbey, is gothic. A writer who enjoyed riffing on literature would naturally be drawn to the genre where making and spotting allusions to other favorite texts is part of the pleasure. Jane Austen completed Northanger Abbey and sold it to a bookseller in 1803. But the novel was not published until 1818, after Austen’s death. It came in a four volume set, a common way to publish books at the time. Northanger Abbey filled the first two volumes, and the second two were Persuasion, Austen’s final novel. This edition fittingly created bookends for her esteemed literary career. Northanger Abbey‘s narrative is in some ways typical Austen fare. The novel follows Catherine Morland, daughter of a country clergyman, as she visits Bath for the season. Balls, flirting, all that good stuff. When Catherine visits the Tilney family at the titular abbey, however, the novel veers delightfully into the gothic. Catherine, a seasoned reader, prepares for the frights she’s sure to encounter at such a location.

The Horrid Novels

One of the reasons Jane Austen stands out among her contemporaries is her writing’s resistance to simplistic interpretations. Practically any passage in Austen is like a fractal, the mathematical figure that can withstand infinite zoom-ins because it yields infinite detail. Take this passage from Northanger Abbey, in which Catherine gets a reading list from her new friend Isabella Thorpe: First of all, get yourself a friend who gives you a reading list as thrilling as this. Second, this dashed off list of titles, known as the “horrid novels,” were especially fortunate to have Jane Austen’s spotlight cast upon them. So what are they? And why these titles? “Yes, pretty well; but are they all horrid, are you sure they are all horrid?” Montague Summers is an important figure in studying the history of gothic literature, notable for his 1938 book called The Gothic Quest. Until he published an article in 1916 with information about the “horrid romances” in Northanger Abbey, these novels were often presumed to be invented by Austen. One has to wonder how many of the horrid novels were already forgotten between the completion of the manuscript in 1803 and its publication 15 years later. In the late 1920s, fully one hundred years after the publication of Northanger Abbey, Michael Sadleir, a British publisher, novelist, and book collector, finally located copies of all seven novels.

Why These Novels?

Finding meaning in this list of novels is a real journey. It should seem fairly obvious in retrospect that the list is composed of real books. If Austen had wanted to concoct a list of novels, she might have come up with even livelier titles. Also, she was probably not aiming to highlight the ludicrous nature of Gothic titles. There were much weirder ones out there, like The Abbot of Montserrat: Or, The Pool of Blood: A Romance or The Abbess of St. Hilda. A dismal, dreadful, horrid story! (That exclamation mark is not my emphasis; it’s part of the title.) Perhaps the titles point to the events in the book itself. Northanger Abbey’s Catherine is a female Quixote, someone who’s read so much it has addled her perceptions of reality. As Cervantes spoofed chivalric romances in Don Quixote, Austen took on the popular literature of her day, gothic novels. But a close look reveals Jane Austen also didn’t choose real titles that winked at the gothic vicissitudes in Northanger Abbey. For example, Catherine uncovers what she thinks is an ominous manuscript but is, in fact, a laundry list. Jane Eyre wouldn’t be published for decades, but in another chapter Catherine is afraid there’s an attic wife situation in the abbey (there isn’t). By these tokens, Austen might have chosen other real gothic titles like The Mysterious Manuscript, or Mysterious Wife to include on the reading list, as Natalie Neill pointed out in her article. So the ridiculous title theory and the self-referential title theory are out.

A Closer Look at One Horrid Novel

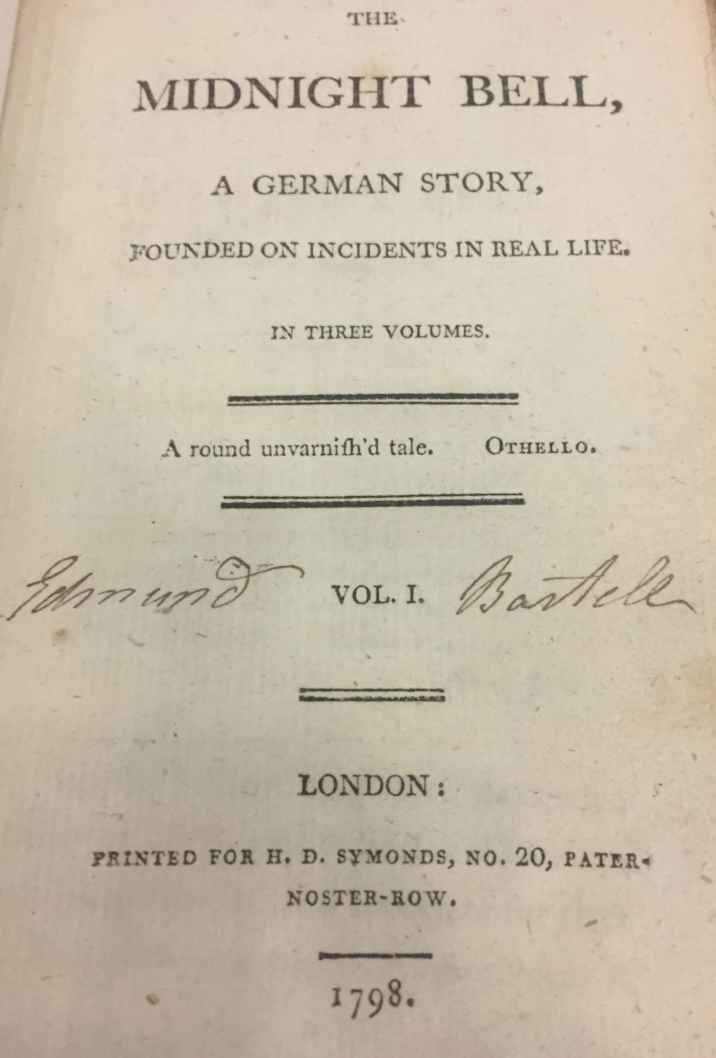

Let’s have a look at one of these horrid novels, so we can glean more information and concoct another horrid theory. I chose The Midnight Bell, by Francis Lathom, published in 1798, because my local rare books and manuscripts library, Indiana University’s Lilly Library, has a copy available for research. The title page provides some important information about The Midnight Bell. The author is unnamed, but anonymously published novels were common at the time. It was eventually connected to Francis Lathom, likely through reviews, ads, or catalogues of circulating libraries that sometimes named authors. The other bits of information, “A German Story” and “Founded on Incidents in Real Life,” are more telling.

Based on True Events

One feature common to gothic literature is an implication of truth that’s just a layer or two removed from the readers. The contemporary equivalent is the “found footage” horror movie, whose purported veracity, even if highly dubious, elevates the fear factor. Sometimes there’s a frame narrative, as with Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw. Another obscure gothic novel I’m fond of, Ellen, Countess of Castle Howel, begins with an “Apology.” It lets readers know the author wrote the novel during a period of great distress. Her writing served to alleviate the suffering she was enduring at the hands of some nameless evil. The Midnight Bell, perhaps a little less ambitious than these other novels, simply tells us it’s real without making more of a fuss. Lack of ambition may in fact typify The Midnight Bell. Like an undergraduate struggling with their term paper’s page requirement, the novel has all the signs of being stretched into its three volumes: large margins, a large font, plenty of spacing between the paragraphs. Lathom himself had contempt for enthusiastic readers of gothic fiction. He said his own novels were “a mere concession to public taste.” It’s no wonder he didn’t put his name on the book. When Montague Summers wrote about Lathom in The Gothic Quest, he claimed Lathom was the illegitimate son of an English peer. Lathom gained some celebrity as an actor, playwright, and novelist. But then he unexpectedly moved to Scotland and took a ten year hiatus from publishing. Summers painted a picture of Lathom, which is not cited with any rigor but is nonetheless quite vivid: a dandified city-dweller mystifying the locals, swilling Scotch and keeping up on London gossip, shacking up with men, and enjoying wealth that possibly came from his estranged father. If The Midnight Bell is the embodiment of unambitious gothic fiction, Francis Lathom himself was the embodiment of the best gothic literature has to offer. His life was both full of secrets and extravagance.

German Stories

The Midnight Bell’s claim of being a German story is perhaps more pertinent than its claim to truth. It definitely fits a gothic trend of the 1790s, according to Neill. Readers were eager for translated German stories, like other horrid novels Horrid Mysteries and The Necromancer. Likewise stories set in Germany, with or without a claim to an original German version, were popular. These include The Midnight Bell, Castle of Wolfenbach, The Orphan of the Rhine, and The Mysterious Warning. Clermont, set in France, is the only horrid novel with no relationship to Germany. Germany’s trendiness in gothic literature at this time is perhaps due to the notoriety and persistence of folklore there. Think castles and forests and witches. Montague Summers, a gothic literature historian, even called the Rhine “the haunted river of the world.” Summers was also a one-man Satanic Panic. He claimed that a secret society conducting Satanic Masses was ravaging Germany in the mid-1700s and inspiring Gothic tales. Given that Natalie Neill described Horrid Mysteries as a “lurid and ludicrous shaggy-dog story about a secret society of vampirish anti-monarchists who perform horrid rites of initiation,” the secret society claim is intriguing, even if there’s little documented history to substantiate it.

Back to Northanger Abbey

Whatever the source of Germany’s thematic popularity, Jane Austen was trying to communicate something with her list of books. One of Natalie Neill’s theories is that these books were especially popular at the time Austen was writing. She simply chose them specifically to highlight the themes in Northanger Abbey of literary taste and consumption. Lovers of Northanger Abbey will remember the contrast between Catherine’s potential matches, John Thorpe and Henry Tilney. John Thorpe says, “I never read novels; I have something else to do.” Henry Tilney, on the other hand, says, “The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid.” And if you haven’t yet read the novel, you can probably guess from these quotes alone how things play out. The setting of Northanger Abbey in Bath makes sense. Bath was famous for circulating libraries, especially that of the Minerva Press. This well-known source of gothic literature published of all the horrid novels except The Midnight Bell. In addition to defending novels generally, Henry Tilney can spin a chilling gothic story on the spot for Catherine. That mirrors Austen’s own background as an unabashed novel reader. A letter from Austen to her sister in 1798 even notes their father was reading The Midnight Bell.

Spoof as Critique

Northanger Abbey may be a loving spoof of novels like The Midnight Bell, but it’s also a critique. By picking on continental novels, Natalie Neill points out that Austen was perhaps emphasizing that the best course for British literature was to prioritize realism. The proof is certainly in the pudding with that theory. The rest of Austen’s oeuvre is realistic fiction that carefully observes the maneuvering of characters within English society. Ultimately, by choosing this particular set of popular gothic novels, Jane Austen has imbued them with a special significance not given to other gothic literature of her time. Who knows how many gothic novels were so well-thumbed at circulating libraries that they were literally read to death? In his book Things Past, Michael Sadleir refers to the horrid novels as “tiny stitches in the immense tapestry of English literature.” He also said that “perhaps such miniature and derisive perpetuity is all that they deserve.”

The Fate of the Horrid Novels

The horrid novels have indeed enjoyed perpetuity. First, their existence as real books was proven. Then, Montague Summers tried to publish a full set of the horrid novels in 1927. Only The Necromancer and Horrid Mysteries made it to print. The Folio Society succeeded at printing the full set in 1968. Valancourt Books released them again in paperback between 2005 and 2015. Instead of thinking of these novels as minute stitches in a grand tapestry, I prefer to think of Jane Austen as a ghostly necromancer, periodically conjuring these books back to life for new generations of readers.