When I recently went back and reread this issue, I was unpleasantly surprised by how racist it is, particularly in the first half. Sure, a certain amount of bigotry is to be expected from older comics (and newer ones, apparently). But the X-Men have been interpreted as a metaphor for just about every oppressed group on the planet—Jewish people, the LGBT community, you name it—and the creative teams have encouraged these readings by deliberately evoking real-world struggles for equality. You’d think such a book would be more careful about their portrayal of the minorities they are allegedly sympathizing with. Instead, they gave us Giant-Size X-Men #1. But let’s back up a second. Here’s a brief summary of the comic in question.

Okay, Not So Brief After All

Almost the entire first half of the book is occupied by Professor X’s recruiting drive. He picks up Nightcrawler from Germany, Wolverine from Canada, and Banshee from Tennessee (ha, it rhymes). Banshee is basically a bundle of Irish stereotypes, so that’s fun. And then there’s Storm.

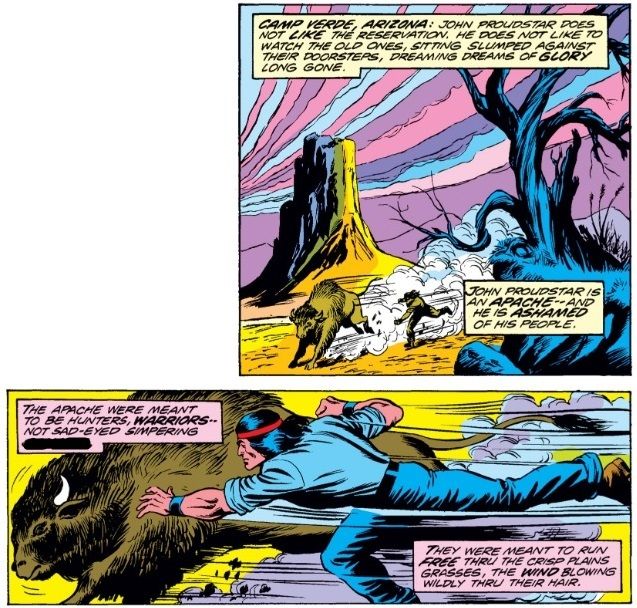

As Joseph J. Darowski notes in X-Men and the Mutant Metaphor: Race and Gender in Comic Books, having a Black character play goddess to a bunch of ignorant, superstitious natives and require a white man to educate her about the true nature of her powers is a touch not good. Next, Xavier goes to Japan to convince Sunfire, a belligerent, West-hating mutant, to lend him a hand. He agrees at first, but later on he changes his mind and skedaddles. He then changes his mind again and returns, only to be incredulously greeted with a racial slur that I thought went out of style after World War II. But that’s skipping ahead. Xavier still must recruit Colossus from the Soviet Union and Thunderbird…well, see for yourself. I had to censor it for you.

Where do I even start. First, this is Thunderbird. He’s the one who will call Sunfire a slur in a few pages. He will also call Professor X various unflattering names related to his whiteness and his disability. He’s not very nice. Second, this is clearly an Arizona desert. What “crisp plains grasses” is he supposed to be nostalgic for? Presumably he means the Great Plains where bison actually live and which are nowhere in Arizona. And finally, as a non-Native, I’m not comfortable diving deep into Thunderbird’s internalized racism, or whatever this is. I can tell you that Len Wein is no more qualified to discuss this than I am, and he definitely should have refrained from putting racial slurs in the guy’s mouth. I should also note that most of the newbies didn’t get to pick their own codenames. Thunderbird actively dislikes his—possibly because it sounds like Professor X came up with it after randomly flipping through an encyclopedia for the first Native-related thing he could find—but too bad. What Xavier wants, Xavier gets. Good thing Wolverine already had his codename, or he’d probably be called Maple Syrup. Cyclops narrates the next part of the comic. He explains that the rest of the X-Men vanished while trying to find a mutant on the remote island of Krakoa. Then we finally get to the actual story: the new team goes to Krakoa, discovers the island itself is alive, rescues the original team, and kills the island in true comic book fashion. The issue ends with them wondering what they’re going to do with so many X-Men. This will not be a problem much longer. Thunderbird dies shortly afterward, and before that, most of the originals as well as Sunfire take off. This comic is fun in its own way. While I’m not a fan of Cockrum’s art, I did like watching the new team come together. Part of that may be hindsight and knowing how important they would become. In any event, I did enjoy some of the issue. But the racism—the depiction of the minority characters, the slurs, and Xavier’s blatant disrespect for their cultures—is such a dark cloud. And this cloud does not hover over this one issue. No, it casts a shadow over the entire X-Men franchise.

Racism, Fantastic and Otherwise

You all know what “fantastic racism” is, even if you’ve never heard the term. It refers to a science fiction/fantasy phenomenon where aliens or other fantasy creatures are used as metaphors to talk about bigotry without bringing any real-world races into the mix. Remember that episode of Teen Titans, “Troq,” where a snooty alien is rude to Starfire because he hates her species so much? That’s fantastic racism. Fantastic racism has been a useful tool for getting heavy themes past censors that were themselves probably racist, or at least willing to pander to racist audiences. The problems start when creators forget it’s supposed to be just that: a metaphor. (If Teen Titans wanted to do an episode about racism, Cyborg is Black and standing right there.) And if the creators can forget the true purpose of fantastic racism, imagine how easy it is for consumers—especially privileged consumers who probably don’t think about discrimination all that often and would most benefit from reminders that it is unacceptable—to forget, misinterpret, or ignore that message. (You do not have to imagine.) The idea that the X-Men are a fantastic metaphor for racial injustice is so ingrained that some have compared Professor X and his archnemesis, Magneto, to Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, respectively. But something about this never sat right with me. This article by Shyminsky helped me articulate why. In brief: the X-Men have historically been a bunch of human-passing, reasonably affluent white people who push for mutant assimilation into human society. Any mutant who isn’t able and willing to assimilate is the bad guy (or at the very least frowned upon, as we’ll see in the next section). This, far from demonstrating that diversity is good and prejudice is bad, makes it easy for non-minority readers to put themselves in the X-Men’s place and view themselves—the white male nerds—as the victims of an unfeeling society, thus undercutting the X-Men’s alleged message of tolerance for all. The X-Men may whine and angst about how persecuted they are and how all they want to do is live their lives peacefully. But at the end of the day, they’re a bunch of superpowered white people who do nothing to promote their own interests or the interests of mutantkind. Giant-Size X-Men #1 was supposed to be their big moment, the moment they finally ceased to be “five upper-middle class white kids,” as Darowski quotes Chris Claremont—who took over writing duties from Wein—saying. But what happens? The Japanese guy quits and the Native guy dies, leaving one African lady in a sea of white faces. Plus the demonic-looking Nightcrawler, of course, but saying the inclusion of a fuzzy blue man promotes “diversity” would be ridiculous. So that’s exactly what Marvel did.

Wait, What?

Mutants are supposed to be minorities. So doesn’t that mean the entire team—despite the fact that they are overwhelmingly straight, white, able-bodied, cisgender, and Christian—is actually super diverse? It’s exactly the same as having a team full of Black people, isn’t it? Obviously not. Even in-universe, mutants’ status as minorities can be dicey, as seen in Avengers #181. For context, the government just took over the Avengers, and they insist on booting almost everyone, including a mutant, in favor of a Black guy because diversity.

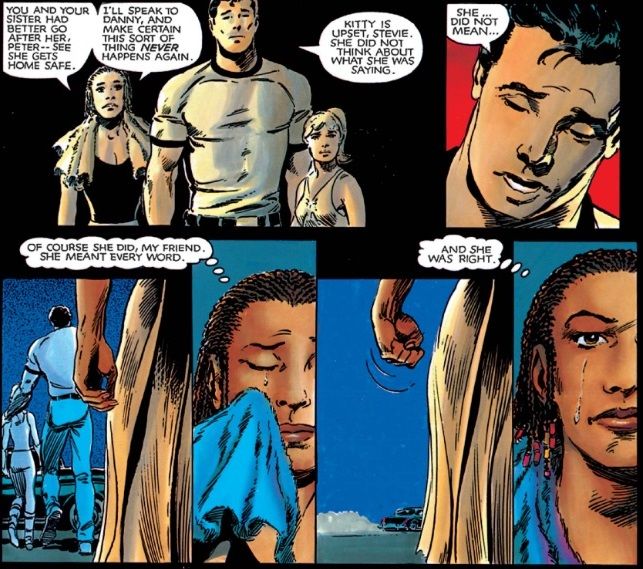

(Note: Quicksilver isn’t the best example here. He and his sister, the Scarlet Witch, aren’t white, so they’d count as minorities whether they were mutants or not. But at the time, the characters had not yet uncovered their true parentage and believed they were white, so we’ll ignore this. We will not, however, ignore the fact that Iron Man just tried to pass off superheroes as a minority. What the hell, dude.) So mutants are apparently not recognized by the U.S. government as a minority group. (Has Xavier, the Mutant MLK himself, ever said anything about this? Legit question here.) Nevertheless, Marvel really ran with this “mutants are minorities” angle. Kitty Pryde, a non-Black mutant who joined the team in 1980, made a habit of using the N-word to convince Black people that being mean to other minorities (specifically mutants) is wrong. The first time this happened was in 1982’s X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills, when Kitty beats up a kid in her ballet class for insulting mutants. Their ballet teacher, a Black woman, doesn’t react as Kitty hoped, prompting her use of the N-word. The aftermath of her outburst was this:

No. No, she was not. I, too, am making the point that hating minorities is bad, and somehow I have done so without using any slur whatsoever. Kitty was a teenager during these incidents, so of course she’s not going to be the most sensitive or thoughtful in her approach. The writers, however, were not teenagers and should have known better than to have her go this route not once, but three times. As for the Xavier-King/Magneto-Malcolm X comparison, it’s downright laughable. Dr. King’s idea of equality was so radical that, at the time of his murder, most Americans disliked and distrusted him. By contrast, it’s a rare day when Professor X so much as hints at mutant rights; traditionally, his focus has been on encouraging and training (in that order) his students to beat the stuffing out of “evil mutants” like Magneto. Far be it from me to speak for Dr. King, but that doesn’t quite seem in keeping with his methods. While we’re on the subject, MLK also didn’t try to force his followers to hide their race, which, if we are to believe “mutation = blackness,” is exactly what Professor X did when Nightcrawler ditched his holographic image inducer in Uncanny X-Men #130.

Giant-Size X-Men #1 takes the metaphor’s shortcomings and makes them worse. Aside from the nameless villagers who want to kill Nightcrawler at the beginning, the only intolerant characters in this issue are the minorities themselves: Sunfire, who hates everyone but the emperor, and Thunderbird, who spouts racial slurs and insults as a matter of course. There’s something very icky about a comic that claims to be on the side of the oppressed while also beating down on the oppressed.

That’s Where It All Falls Down, Of Course

Maybe I’m not the best person to be talking about this. I’m not a member of any of the races disparaged in this comic, and while I enjoy the X-Men comics I’ve read, I don’t consider myself a serious fan. It’s possible I’m missing some nuances here, either because of my race or because I’ve read a comparatively limited number of the comics. That said, I am a minority, I love superheroes, and nothing ticks me off faster than opening a comic and being slapped in the face by stupidity. If nothing else, I hope this serves as an adequate content warning for those who want to read Giant-Size X-Men #1 for themselves. Honestly, that was my reason for starting this article. This is such an iconic issue that I figured a lot of people may want to read it, only to end up as blindsided as I was. But the more research I did, the more I came to the conclusion that the X-Men being stand-ins for [insert minority of your choice here] is confusing at best and outright harmful at worst. In fact, why is Marvel still using this metaphor? Maybe fantastic racism was the only way to confront the subject in 1963 when the X-Men were created, but we’re well past that now. Marvel can create as many minority characters as they want. Why keep using mutants, an easily misinterpreted and misused stand-in, for stories about prejudice when you can deal with such matters directly? Is it even possible to divorce the X-Men from their subtext at this point? I don’t know the answers to these questions, but the bottom line is this: X-Men cares more about fantastic racism than actual racism. The metaphor has broken free and devoured its own point. Giant-Size X-Men #1 may have given the team a new line-up and a new lease on life, but they immediately went back to their same old BS. If the X-Men are minorities, they are “the good ones,” the ones who try to fit into the dominant culture, who spend an inordinate amount of time defending their oppressors from the “bad” minorities, and who don’t agitate too loudly (or at all) for equal rights. And if that’s supposed to be a metaphor for race and racism, I don’t want it.