We are about to enter the realm of discussing Legend of Korra, so I have to put this warning up:

Avatar: the Last Airbender is a story about children having to fight in a war they never wanted. Certain people can use the elements of nature via “bending,” and the Avatar can bend fire, earth, air, and water to bring peace to all nations. In Aang’s case, as the Avatar he has to save the world, but that means forcefully shedding his old life. Katara and Sokka have faced the consequences of losing their mother to a raid and their father to the front line. Toph could choose to leave the war alone, but she decides to dive in to find her purpose rather than stay her father’s protected princess. Then we have Zuko, and his sister Azula. Zuko dives into the war because he needs the Avatar to return home. He serves as an antagonist, because he wants to capture Aang and turn in him with no thoughts to the consequences to the world. Azula enters the story to capture her brother and humiliate him for his failure. She soon develops bigger plans, and is even more dangerous; while Zuko has some moral limitations, Azula has none. Meanwhile, their father Emperor Ozai looms over the story, motivating the Fire Nation to conquer and burn.

Avatar: The Last Airbender is remarkable. We have a cast of all POC characters, if not POC voice actors, with lots of story arcs that weld lore, previous plot points, and humor melding with tragedy. The main characters and minor ones witness war, and have to fight against it but try to find joy and peace despite their problems. Prince Zuko has the best redemption path that more stories would do to emulate. With that said, has its flaws. As Twitter has pointed out, it’s a show with two white creators that borrows liberally from Asian culture. Fans agree that “The Great Divide” is probably the worst episode, due to rather contrived writing and a cheap resolution. Despite the flaws, people can rewatch the show and enjoy it lore, as well as its character development. Sokka goes from being an arrogant, ineffective warrior to a formidable leader, to the point that Azula sees him as a threat. The question then become, what happens after the show? What could the creators say, after penning one of the best stories in Western media? The answer, or rather the attempt, became The Legend of Korra. We see a new Avatar, and a rather different journey.

Telling A New Story

Korra is Aang’s reincarnation, born during a prosperous time. Rather than a tiny village of ice houses, the Southern Water Tribe has become a formidable world power again. Korra also found out who she was as a toddler, and has received training since, locked away from the world and from her oncoming duties. She has inflated arrogance and confidence about who she is and what she will become. Then the rest of the seasons shatter that ingrained belief, and shape her into a different person. She comes out of her experiences wiser, sadder, and a touch more realistic about the world’s problems. The series seeks to answer this question: does the world need an avatar? Korra, the more she travels, fears that isn’t the case. Her enemies want her to not exist, or to use her as a weapon. They destroy her, bit by bit. In the meantime, her allies had to build a new world without her. She doesn’t even know how to navigate relationships, or to negotiate in bitter family feuds. As the creators explained, they didn’t want to repeat The Last Airbender‘s story, of war. They wanted a new story, of a new Avatar, whose journey would go down a different direction. The problem is that in doing so, they stripped a lot of the elements I liked from the first series. While I understand the creators were trying to make a new Avatar series, without repeating old beats, their attempts didn’t speak to me. They spoke to my friends, who related to Korra’s desire to find her place in this changing world, and how her expectations change with circumstances. I’m not in the right time and place to accept these messages.

The Good Things about Legend of Korra

First, we have a female lead who is a woman of color and bisexual. She ends season one dating a guy, and ends the series going out with a girl. Considering the stigma in Western media against LGBTQ relationships, and that Brooklyn 99 is the only live-action show with a bisexual lead, this is a huge plus. Second, we have a character that faces trauma in a realistic manner. Korra develops PTSD from the end of season three, and it takes years for her to recover. I don’t agree with the methods, with reasons I’ll outline below, but I appreciate that the show portrays the hard road to recovery, and how it’s not a linear line. Third, we see a bigger Avatar world and lore. Korra learns how the first Avatar came to be, and why the spirits and humans don’t get along. The Fire Nation goes in a more pacifist, constructive direction than it did under Ozai’s reign. Technology develops in line with bending, as does art, music, and sports. Governments do as well, for better or for worse. They have to change with the times, sometimes rapidly. Fourth, the villains are morally ambiguous. They start with good intentions that quickly go downhill, and prey on those who need help. Ozai and most of the Fire Nation villains straight up want to burn people and destroy them for the sake of conquering, and Zuko—despite his good intentions—still does a heap of terrible things. Here, people like Amon, Unalaq, Zaheer and Kuvira fall victim to extremism, and becoming the beings they hate, or tempted into grabbing more power than they can handle. In the case of Zaheer, he doesn’t have long-term plans that end up imploding in the long run.

Changing Losses

Aang loses his entire world before his series starts. A runaway avatar who didn’t want to shed his playful life or friends to commit to duty, Aang fled from the air temple before the monks could take him from his friend Monk Gyatso. Then a storm enveloped him and his bison Appa for a hundred years. When he wakes up just outside Sokka and Katara’s village in the South Pole, he immediately asks Katara if she wants to go sledding and doesn’t realize how much time has changed. When he realizes that he’s been asleep for a hundred years, his first thought is his room is all messy and if he survived the Fire Nation, then other Airbenders have been as well. To his dismay and shock, he finds Gyatso’s body next to Fire Nation soldier corpses in an abandoned Air Temple. Snow covers all the statues, and no air bender has survived. After understandably having a freak out, Aang calms down after Katara comforts him. He realizes that he cannot avoid his destiny, or find his old life. Aang embraces saving the world from the Fire Nation, and defeating Emperor Ozai. Korra, in contrast, faces her losses more gradually. In Republic City, for example, she finds out that a girl and a polar bear dog can not get food if they lack money or knowledge of park regulations. Then she finds out that a mysterious extremist named Amon kidnaps benders and de-powers them. Claims that he can remove people’s bending, preying on those whose claims against benders are legitimate: there are bending mob men, athletes who will cheat in professional games, and even reckless Avatars like Korra who mean well but cause destruction. Amon targets the Avatar after he destroys her reputation, and he makes good on that promise to wait until the public has a low opinion of her. She’s not at the point where she can talk down her enemies. Getting to that point takes four whole seasons.

Spectrum of Evil

The first series made it clear that while most Fire Nation soldiers were brainwashed and conditioned into storming through villages, the ones we saw who conquered and killed needlessly faced consequences. General Zhao faces permanent imprisonment in the spirit world for trying to kill the moon, as one example. Yon Rha, the general who murdered Katara and Sokka’s mother in cold blood, has to beg for his life from a vengeful Katara. Iroh lost his son while trying to conquer Ba Sing Se for the Fire Nation and Zuko realizes that he has to switch sides, but takes a long time to convince the heroes that he has truly changed. They understandably take a while, since his actions led to Aang dying once. No one is above the consequences in this case. What’s most fascinating and infuriating is that we don’t see the consequences that ordinary citizens face for allying with Amon. The rich like Hiroshi Sato end up in jail, and Amon dies with his brother in a boat explosion as they flee for their lives. They seem to escape the consequences that Amon faces once Korra unwittingly defeats him. Many are ordinary citizens who demand a better life, but will hurt others to achieve their goal. They also cheer on seeing children put on display for this spiritual execution. Yet, come season two, we don’t hear of them being arrested or facing consequences for advocating a form of genocide. The one who suffers the most consequences actually is Asami Sato, a normal non-Bender whose father joins Amon, and when she turns on Hiroshi to save Korra and her boyfriend Mako, she loses her formerly posh life and status. It’s so unfair for such a sweet and forgiving character, while faceless criminals get off the hook.

The Double Standard

There’s a double standard that Korra loses all of her confidence and ego to ongoing trauma, while Aang is allowed to remain a child even as he faces the ramifications of war. By the end of the series, she has changed into a different person, and she attributes that to all the pain and trauma she endured that gave her empathy. You don’t need to suffer to have empathy for another person. That should be plain common sense. We can understand others’ problems without needing pain and loss. By this, I don’t mean pain that life slings on us, like natural disasters, but the pain that other people inflict upon us, within their control.

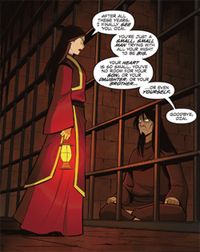

The scene that defines why I dislike Korra is when she confronts one of her abusers, the anarchist Zaheer. Zaheer was a Red Lotus member that wanted to indoctrinate Korra when she was younger; he then tried to murder her and destroy the Avatar cycle completely. Korra survives but suffers physical and emotional trauma for two years, to the point that no one takes her seriously after a failed battle. Zaheer is captured alive and imprisoned; she goes to him to overcome her reasonable fear of him. She’s still afraid, despite his chains and shackles, and he tells her he knows she hasn’t reached the Spirit World. What’s more, he refuses to take responsibility for his actions in scarring her, only saying she’s blaming him to have a crutch. Korra reluctantly accepts his help to return to the Spirit World, and to do so he makes her relive the murder attempt, while telling her to accept what has happened since she cannot change it. Let’s contrast this to a scene where Zuko confronts his father, the main villain of the first series. Ozai scarred and banished Zuko for speaking out of turn, which led to Zuko chasing Aang for two seasons and trying to win his father’s love. Throughout season three, Zuko seems to gain that affection but questions why the victory feels hollow. Ozai sees his son more as a status symbol than as a child. Zuko eventually realizes that Ozai isn’t worth it, and prepares to sever ties.

Zuko confronts his father during the fateful eclipse, when neither of them can use fire but Zuko can use his swords. The prince calls out his father for scarring him as a child, and saying that making him suffer to learn a lesson was wrong. Ozai retorts that Zuko learned nothing, which sets off Zuko on a rant about how everyone hates the Fire Nation for being colonizing tyrants, and they aren’t the heroes as their teachers taught them. Zuko vows to be nothing like his father, and more like his compassionate uncle Iroh, who was imprisoned for helping the Avatar and his friends escape last season. Then Zuko leaves in style, deflecting his father’s attempt to murder him. He will not tolerate his father’s abuse, while making amends for his costly mistakes and sins. Even the body language in both scenes is different. Korra understandably cringes from her imprisoned attacker, while Zaheer stands tall and sanctimonious in chains. Zuko faces his father with blades in hand, while Ozai sits at first. There is a difference, especially when Zuko takes charge of his life and destiny. The comics follow suit, when Zuko’s mother confronts her ex. Zuko got permission to deny his abuser any power over him. Korra doesn’t. She only gets in one good point—that by destroying her and a dictatorship in the Earth Kingdom, Zaheer ended up creating the thing he hoped to avoid: another tyrant. Zaheer doesn’t acknowledge that he ruined her, only asserting that she’s stronger than she thinks because she survived his murder attempt, and that he can sense her power. That creates a strength imbalance between them.

A Show Worth Watching

Despite my nitpicks, I’m happy The Legend of Korra exists. It wasn’t what I wanted, but it was what people needed. Viewers needed the stories told. The show paved the way for LGBTQ subtext to become text, as shown with Steven Universe, the finale of Gravity Falls, and Adventure Time. Plus, its fans got an adventure, and quite a few rides. I’m hoping that any future shows will learn from Korra’s mistakes, and tell a story where a bisexual POC female or nonbinary lead doesn’t need to break to develop character and strength. We have to accept the progress that happens, however, and enjoy what we have for the moment, and its predecessors.

![]()