If you’re not willing to do those things, then stay in your own lane because people who think the whole world is up for their grabs have already done plenty of damage, and no one needs any more of your appropriative “it was just a bit of fun” takes. I see you wondering why I think I have the right to say anything about this and that’s fair. Here’s the thing: surface, I look like a lot of other ally-type early-middle aged ladies, but I grew up in a Conservative Jewish household. So when I see folx casually slinging golems around or saying sure, Oscar Isaac would make a fantastic Moon Knight (that’s an “M” preview for you)…hnnngh. And while no, it is certainly not to the same extent other cultures have had their very souls appropriated. But it does poke me in the lizard brain and engage lock-down. So. What I’m going to do in this A–Z is look at fairytales, folktales, and myths from a different direction (and a couple of different angles): I’m going to look at stories that are either western in origin that have been reimagined through other lenses, stories that were coopted and have now been retold by the people to whom they originally belonged, or upcoming stories about which I’ve noticed people voicing concerns for culturally linked reasons. There do seem to be some cross-cultural ur-stories (e.g. great floods, the taming of primordial chaos, and oddly, vampires?) that I’m planning to stay away from since they’ve already been fed through a truly staggering number of cultural lenses. If I tend toward manga it’s because that’s what I’ve read most widely in comics originating outside of the U.S. so far, but I am actively working to widen my perspective and hey, if you have any recommendations, please send them to @BookRiot. Alright, here we go!

A: Aladdin

B: Beauty and the Beast

C: Celestials

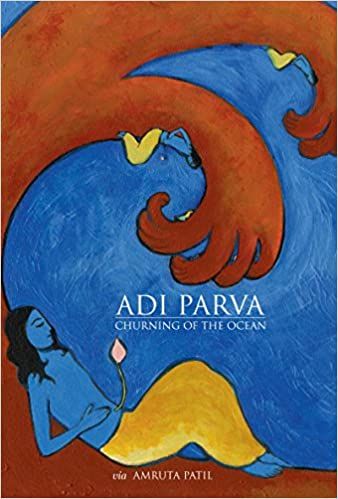

D: Durga

See. It’s out there. You just have to put in the time to look. Y’all don’t have that time; that’s why you have me.

That’s a lot of degrees of separation.

I did some digging and found several prose translations and interpretations of “Aladdin and his Wonderful Lamp” done by Arabic-speaking writers and scholars, but neither graphic novels nor comics—I’m not sure whether or not this has something to do with the subject matter, the prohibition on certain types of images, or if it’s simply that no one has gotten around to it yet. Alas, I didn’t find any versions illustrated by Chinese or Indian artists either (they may very well be out there and not have English translations).

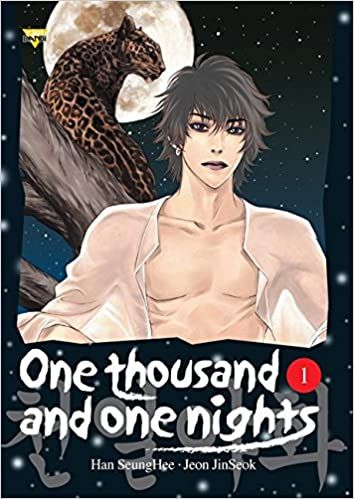

I did find a Korean reimagining of the Thousand and One Nights frame narrative that looked interesting, and that, I hope, might provide some insight into how a non-western culture views the story of the lazy tailor’s son who lucked into magic he didn’t deserve and won a princess despite his initial muppet flailing. And how that story bought Sheherazade one more night.

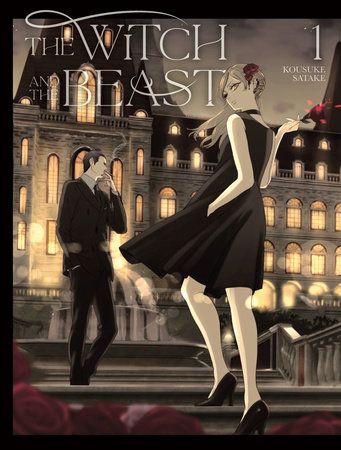

The Witch and the Beast is a version of Beauty and the Beast in which the beast is subject to the beauty, in which he depends upon her for survival. It is a story in which magic is a weapon women wield when they are wronged and to which men are subject because, quite frankly, they deserve it. Slick, stylish, a little terrifying, and, in my opinion, more than a little satisfying, I’ve already preordered the other five volumes of Satake’s fractured fairytale.

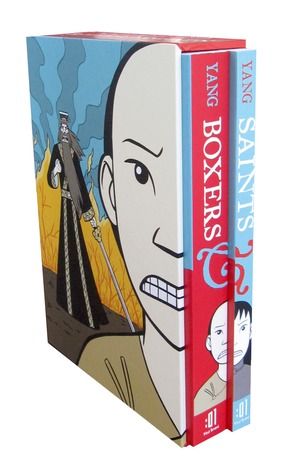

Safe to assume Gene Luen Yang and Lark Pien are a little more careful and a great deal more knowledgeable in their depictions of the gods who appear to Little Bao and urge him to take up arms against the missionaries and colonizers who have plundered his village, leaving his people with no choice but to fight for survival.

Yang also deliberately flipped the script used in older comics in using gibberish language where the script is portraying a foreigner attempting to communicate with a Chinese speaking character as it was important to him that this story be told from the point of view of Chinese protagonists.

Take that, interlopers.

Who know’s how far we’ll go.