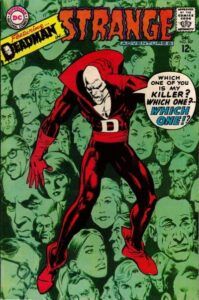

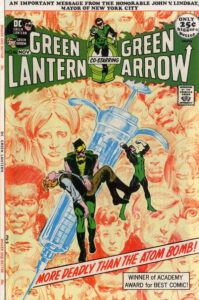

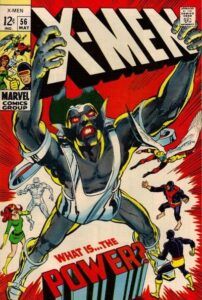

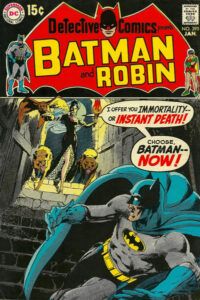

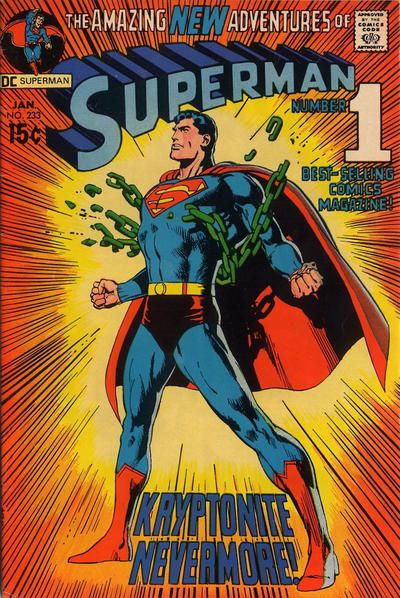

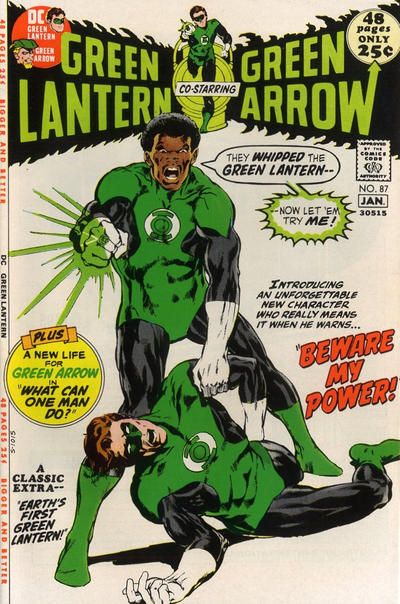

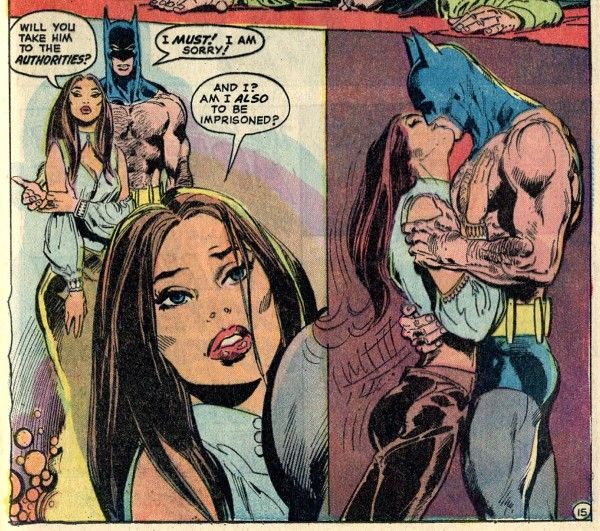

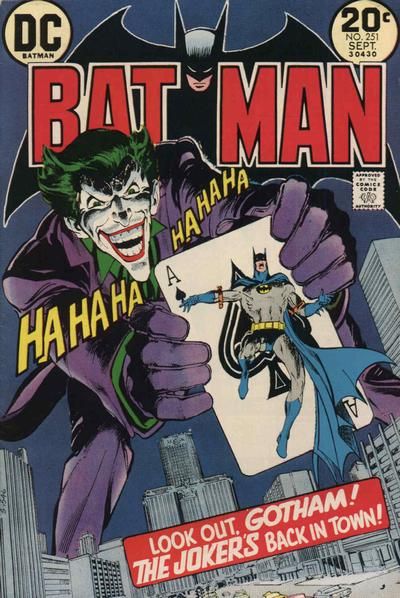

Adams was a legendary comic book artist best known for his groundbreaking work in the 1970s, during which he helped to revitalize Batman and introduce more mature and complex themes to superhero comics, as well as co-creating one of DC’s first Black superheroes, Green Lantern John Stewart. He was also an early and vocal advocate for creators’ rights. Adams, who was Jewish, was born on Governors Island in New York on June 15, 1941. After graduating from the School of Industrial Art high school in 1959, he began his career drawing superheroes for Archie Comics and soap opera strips like Ben Casey for the Newspaper Enterprise Association syndicate. He started freelancing for DC Comics in 1967, where some of his earliest work involved taking over the art on the brand-new character Deadman, a trapeze artist who is killed during his act and becomes a ghost with the power to possess living beings. Though Deadman was created by Arnold Drake and Carmine Infantino, Adams remains the artist most strongly associated with the character to this day. In late 1969, Adams began collaborating with writer Denny O’Neil on Batman. At the time, the character’s portrayal in the comics matched the goofy camp of the 1966 TV show starring Adam West, which had been canceled in 1968. O’Neal and Adams wanted to bring Batman back to his roots as a dark, brooding hero, something for which Adams’s art was perfectly suited after honing his realistic style on soap opera strips. They began their collaboration with “The Secret of the Waiting Graves” in Detective Comics #395 (January 1970) and would go on to revamp A-list Batman villains like Two-Face and the Joker into serious threats in stories that are still considered landmarks today. They created one of the DCU’s most prominent villains, Ra’s al Ghul, as well as his daughter Talia, in “Daughter of the Demon” (Batman #232, June 1971). Adams also co-created the reluctant villain Man-Bat with Frank Robbins in 1970. The O’Neil and Adams team also took over Green Lantern in 1970 with issue #76, bringing in Green Arrow as a co-headliner. Their iconic run marked one of the first — and still one of the most famous — instances of superhero comics very explicitly addressing relevant social justice issues such as racism, pollution, and drug addiction. In the landmark story “Snowbirds Don’t Fly” (#85), it was revealed that Green Arrow’s sidekick, Speedy, was addicted to heroin — a sympathetic treatment of what was then a deeply taboo topic, and one which earned DC a letter of commendation from then–NYC mayor John Lindsay. In #87, they introduced DC’s second-ever Black superhero, the new Green Lantern John Stewart. Adams later recalled advocating with editor Julius Schwartz to introduce a Black Green Lantern because he found it implausible that every hero selected by the supposedly unbiased Green Lantern rings would be white. During this period, Adams somehow also found the time to freelance for Marvel on X-Men and Avengers stories. Aside from his art and the many groundbreaking stories he drew, Adams was known for being a vocal advocate for creator rights, which is still a fierce battle. Freelance writers and artists who do work for hire for DC and Marvel have no legal ownership of the characters they create, the stories they tell, or, before Adams, even the physical art they produced, even as the publishers’ parent companies pull in billions of dollars of profit based on creators’ work. Adams was instrumental in changing industry practice so that publishers began returning original art to the artist, rather than destroying it once the comic was printed; this provided an additional income stream to artists, who could then sell the original art to collectors, a thriving practice that can still be seen at any comic book convention today. He also helped Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster receive long-overdue credit and (some) compensation from DC. In 1978, Adams helped form the Comics Creators Guild, and in 1984, he founded his own comic book company Continuity Comics, which lasted until 1994. He also championed an effort to have the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum return the original artwork of Dina Babbitt, a Holocaust survivor who had been forced to work as an illustrator for Josef Mengele, though he was always careful to distinguish the atrocity of the Babbitt case from his advocacy for more prosaic creator rights. Among the many awards he won over the course of his career, Adams was inducted into the Eisner Awards’ Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 1998, the Harvey Awards’ Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1999, and the Inkwell Awards Joe Sinnott Hall of Fame in 2019. Superhero comics would not be what they are today without Neal Adams. Not only is his distinctive artwork with its lean, kinetic realism and deep and moody shadows instantly recognizable, but his work ushered in greater diversity and complexity of ethical themes, and paved the way for the famous “grim and gritty” comics of the 80s. Every Batman adaptation from Michael Keaton to Robert Pattinson cites Frank Miller’s work on Batman: Year One and The Dark Knight Returns, but there would be no Miller without Adams (who mentored him). More importantly, he was a champion for respectful representation of marginalized and disenfranchised people. Though his work from 50 years ago can sometimes seem dated today, his good intentions are clear. And his fight for creator rights has left a lasting legacy. “When he saw a problem, he wouldn’t hesitate,” his son Josh Adams told The Hollywood Reporter. “What would become tales told and retold of the fights he fought were born out of my father simply seeing something wrong as he walked through the halls of Marvel or DC and deciding to do something about it right then and there.” At the end of the day, words can only do so much to explain why a visual artist’s work matters, so I’d like to close with just a sampling of Adams’s most iconic art: