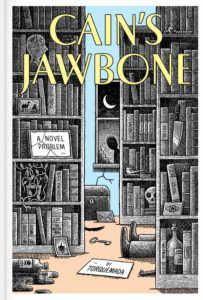

At the time, puzzle books weren’t uncommon. I remember an interactive puzzle book about the Famous Five, and another one about British comic hero Biggles. I also remember the Usborne Puzzle Adventure series, where I lived through the Intergalactic Bus Trip, the Time Train to Ancient Rome, and the Escape from Blood Castle. Those were the good days, tucked into corners in my parents’ house and escaping into detective adventures that felt incredibly real to my little head. When I was in the thrall of these fictional victories, my father told me a legendary tale; a book he had heard about when he was a child, whose pages were separated. There was a prize, he said, for anyone who could piece the book back together. I grew up. I left my puzzle books behind in favour of hefty nonfiction, school books and legal texts. But a few months ago, something popped up on my Twitter timeline and everything came rushing back. Cain’s Jawbone, it said. A new book to be printed by Unbound. One hundred individual pages of a novel, which the reader must put in order to understand the greater picture of the book. Cain’s Jawbone is a legacy from an older time—in 1934, the man who wrote the Observer’s cryptic crosswords published a novel where all the pages were printed in the wrong order. It was possible to reorder them, but it would take intelligence and logic to get to the finish and discern the perpetrator of the six different murders which occurs within its pages. There are two recorded solutions of the mystery, which has millions of possible combinations—and only one is right. The story was reborn through Unbound and crowdfunded to release. My arrogant self thought that I would solve it easily, but reader, it has confounded me from the outset. The book arrived as a series of 100 cards, boxed inside a pretty illustrated presentation box. A small booklet gives guidance and basic information. The novel is written in a formal English style and the pages without context are prone to boring a reader to the point that they might miss something incredibly important. It’s not easy to place any of the pages in their right places and even following some stretches of thought can be tricky because of the differing viewpoints and happenings. There’s a fascinating article on Cain’s Jawbone at the Guardian which explains how the Unbound project came to fruition. Alan Connor received a copy of the 1934 text from an acquaintance and later sought help to solve it in the pages of the newspaper. Having made a connection that satisfied him of the solution, and together with the Laurence Sterne Trust museum and a lucky meeting with a QI producer, Unbound picked up the book for crowdfunding and publication. I wonder if a reader could solve it?