Almanacs, as it turns out, have been around the Americas since the 1600s. Their popularity, though, grew most in the 1700s when the publishing capabilities spread to a larger group of people than before. Almanacs were much cheaper to produce than novels or other literature, so many took to trying their hand at these short, informational publications. One of the most popular and influential almanacs was Poor Richard’s Almanac.

Creation

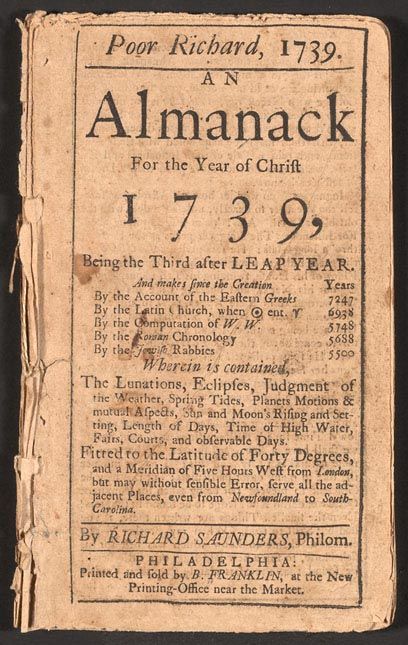

Many of Benjamin Franklin’s inventions are well known. Bifocals, the lightning rod, the Franklin Stove, and the list goes on. But maybe lesser known is his Poor Richard’s Almanac. Using the pseudonym Richard Saunders, Franklin published his first almanac on December 19, 1732. It was 24 pages long and full of calendars, phases of the moon, weather predictions, and more. He wasn’t alone in the almanac publishing business. At the time of his first publication, there were already five almanacs circulating in Philadelphia alone. They were easy to write and publish and over 60% of households in the colonies bought one version or another. The almanac business was booming and Franklin was joining in.

Content

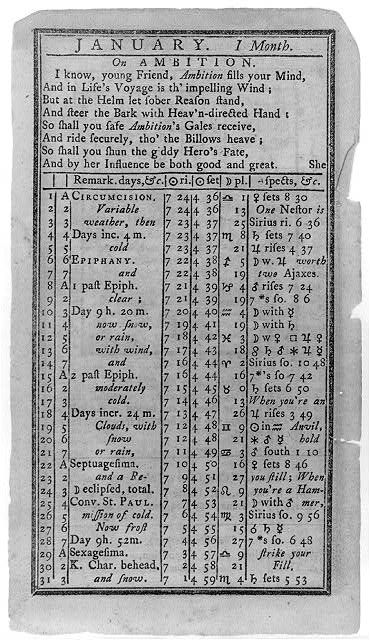

Almanacs in the 1700s consisted mainly of weather forecasts, phases of the moon, sunrise and sunset times, road conditions, court dates, and the like. They were instructional, and sometimes speculative, pieces of literature for the masses. Due to their simplicity, many also used almanacs to teach their children to read. They were some of the most read books in the colonies. Franklin saw them as vehicles of “instruction for common people” who were unable to afford the more expensive novels and other literature. You might wonder why any one almanac would be more popular than others if they had all the same information. Poor Richard’s Almanac set itself apart in two ways. First, it took a humorous tone, setting it apart from its competition. The name “Poor Richard” comes from the narrator of the publications who introduced each almanac. He was sharp and funny, in his first introduction citing a nagging wife as his reason for writing these almanacs. He wanted to make some money to get her off his back. In the same issue, Poor Richard, and by extension Franklin, jokingly started a conspiracy theory, saying his “friend” Titan Leeds, an actual rival almanac publisher at the time, would die soon and no longer pose a problem to his publication. Leeds, however, remained very much alive. The hoax continued through subsequent issues with Poor Richard saying Leed’s ghost was haunting him through the publishing of “almanacks in spight of me and my predictions.” This sense of humor entertained an audience used to purely informational almanacs. They were hooked. Second, Franklin’s almanac also covered a wider range of topics than his rivals, including recipes, philosophical discussions, proverbs, anecdotes, mathematical puzzles, and serial-style stories that encouraged readers to purchase subsequent issues to find out what happened next. He published jokes and conspiracies, like Leed’s supposed ghost. Franklin’s almanacs weren’t only to inform. They were also to entertain. In the end, that’s what made them so popular.

Popularity

Poor Richard’s Almanac rose in popularity until it was the second-most purchased publication of its time, beat only the Bible, with sales rates landing somewhere around one almanac for every 100 colonists. It sold around 10,000 copies a year. Franklin’s humor and ability to “spice the prosaic matter of the ordinary almanac” made his publication more popular than those around him. His almanacs were selling like wildfire. Poor Richard’s Almanac was so popular that, as the story goes, Napoleon had it translated to Italian. It was later translated into French too.

Proverbs

Many of the proverbs published in Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac are still recognized, and used, today. Ever heard, “early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise”? How about some variation of “fish and visitors stink after three days”? The list goes on. “God helps them that help themselves”, and “tart words make no friends: a spoonful of honey will catch more flies than a gallon of vinegar”, and “no pain, no gain”, and “three may keep a secret if two of them are dead.” I’ve heard variations of all of these through my life and I’m sure you have too. Years after Poor Richard’s Almanac stopped being published, critics of Franklin accused him of stealing these proverbs from other sources. However, Franklin acknowledges this very act in his autobiography saying he took them from the “wisdom of many ages and nations.” Poor Richard in the 1746 almanac also admits to his borrowing as he is “no poet born,” asking, “why then should I give my readers bad lines of my own, when good ones of other people’s are so plenty?” Other almanac makers, too, took literature, poetry, or phrases from other authors and used them in their own publications. It was common practice at the time. In defense of the borrowing, many of these proverbs are spread even today “only because of the fame of the ‘almanack-maker’ Benjamin Franklin.”

The End of Poor Richard

In 1748, Poor Richard’s Almanac became Poor Richard Improved as Franklin made the publication larger (and more expensive). In these later editions, Franklin added more of his own thoughts on morality, financial savviness, and industry for people to learn from through the mouthpiece of Poor Richard. Ten years later, in 1758, Franklin concluded Poor Richard before moving off to England. His final issue included a speech by a new character, Father Abraham, who gave a speech that was essentially a compilation of business and life advice published in previous Poor Richard issues. This speech was published separately later and titled The Way to Wealth which became one of the most popular publications in 19th century America. It was reprinted across multiple languages and distributed around the world. Poor Richard’s Almanac and The Way to Wealth are credited as the spark for a generation built on Franklin’s ideals. So many read his moral and business advice, society adapted to reflect these in coming years.

What came after?

After Poor Richard’s Almanac’s end, Franklin left a hole in the almanac publishing world that many sought to fill. In its wake, dozens of publications sprung up inspired by Poor Richard in an attempt to achieve such success. Many mirrored his titling, the use of the name Richard, or developed their own witty characters to try to appeal to the same readership. In 1801, Carey’s Franklin Almanac was published in Philadelphia. In Connecticut, Poor Richard Reviv’d appeared the same year. Others with titles like Franklin’s Legacy or The Franklin Almanac made an appearance on the scene. Many of these referenced Poor Richard, Father Abraham, or Franklin in their pages. They were, all of these publishers, making tribute to Franklin and his impact. He is, to some, “America’s most famous almanac maker.” Did you enjoy reading about Benjamin Franklin and his Poor Richard’s Almanac? Why not keep the spirit of the almanac going and learn about something new? Do you know the history of book blurbs? Or how about a brief history of reading through the ages? Whatever you do, you’ll now know the answer to that trivia question sure to stump everyone else about who it was who published Poor Richard’s Almanac and where all those pesky proverbs come from.